Every year as NCTE approaches, I find myself wishing it was held at another time of the year—some time when things don’t feel quite so hectic, with the holidays looming, my work ramping up and a book still to be done. But this year in particular NCTE was exactly what I needed: the perfect kick-off to the holiday season and a great kick start for writing, with so many people giving generous gifts of wisdom, inspiration and joy.

Talk of joy, in fact, was so prevalent that my wonderful colleague and session pal Kathy Collins warned us not to talk about it so much, lest it become the next new thing, like grit, to teach, complete with lesson plans, assessments and rubrics. But another pattern I noticed in the sessions I attended was the importance of process. In a session titled “Rethinking Our Thinking: The Role of Revision in Writing and Reading,” for instance, Georgia Heard, Ralph Fletcher and Dan Feigelson put process front and center as they shared a range of ways to consider and help students embrace revision as, Naomi Shihab Nye puts it “a beautiful word of hope,” that’s integral to the process of both reading and writing.

Process was also at the heart of a session called “The Art of Knowing Our Students: Action Research for Learning and Reflection,” which was chaired by Matt Renwick. The first speaker Karen Terlecky shared the Appreciative Inquiry process—and showed how it could transform the way we think about meeing professional goals, not as something to achieve but something to inquire into and explore. And Assessment in Perspective authors Clare Landrigan and Tammy Mulligan offered a process for thinking about and looking at formative assessment that can help us move beyond beyond raw data to the living, breathing child beneath the numbers.

Process was also at the heart of a session called “The Art of Knowing Our Students: Action Research for Learning and Reflection,” which was chaired by Matt Renwick. The first speaker Karen Terlecky shared the Appreciative Inquiry process—and showed how it could transform the way we think about meeing professional goals, not as something to achieve but something to inquire into and explore. And Assessment in Perspective authors Clare Landrigan and Tammy Mulligan offered a process for thinking about and looking at formative assessment that can help us move beyond beyond raw data to the living, breathing child beneath the numbers.

Additionally, process formed the heart and soul of a gorgeous session presentation by Randy and Katherine Bomer. Called “Tracing the Shape of Human Thinking: Reclaiming the Essay—and Writing about Literature—as Complex and Beautiful,” Katherine began by making an impassioned plea to return the essay to its original intention, to explore something through a journey of thought (i.e., a process), rather than to argue or prove. And Randy invited us all to attend to our own journey of thought as we drafted and revised our thinking about poet Li-Young’s devastatingly haunting poem “This Hour and What Is Dead.”

Additionally, process formed the heart and soul of a gorgeous session presentation by Randy and Katherine Bomer. Called “Tracing the Shape of Human Thinking: Reclaiming the Essay—and Writing about Literature—as Complex and Beautiful,” Katherine began by making an impassioned plea to return the essay to its original intention, to explore something through a journey of thought (i.e., a process), rather than to argue or prove. And Randy invited us all to attend to our own journey of thought as we drafted and revised our thinking about poet Li-Young’s devastatingly haunting poem “This Hour and What Is Dead.”

But perhaps what stood out the most for me was the way the whole Convention seemed to be the result of a process that we, as educators, went through over the last several years as we sought—and fought—to find our voices in the age of mandated education reforms and the supposedly objective supremacy of data.

Only three years ago, for instance, the only whisper of push back I heard (at least in the sessions I attended) came by way of the teacher and cartoonist David Finkle. In a five-minute presentation called “Pay Attention to the Man Behind the Curtain,” David shared a classic scene from The Wizard of Oz, which he used to question the authority and wisdom of the man behind behind the curtain of the Common Core Standards, a.k.a., David Coleman. At that point, however, like Harry Potter’s nemesis Voldemort, he seemed like a “He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named” specter—someone who’s so powerful his very name could unleash dark forces.

Only three years ago, for instance, the only whisper of push back I heard (at least in the sessions I attended) came by way of the teacher and cartoonist David Finkle. In a five-minute presentation called “Pay Attention to the Man Behind the Curtain,” David shared a classic scene from The Wizard of Oz, which he used to question the authority and wisdom of the man behind behind the curtain of the Common Core Standards, a.k.a., David Coleman. At that point, however, like Harry Potter’s nemesis Voldemort, he seemed like a “He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named” specter—someone who’s so powerful his very name could unleash dark forces.

And now, three year’s later, here’s a stand-out moment from a stand-out panel discussion called “Expert-to-Expert: On The Joy and Power of Reading.” Chair Kylene Beers ended the session by asking the three panelists what policy changes they would make to ensure that schools become the place we all want them to be. And without missing a heartbeat, here’s what each panelist said:

Kwame Alexander, the author of this year’s National Book Award winner The Crossover, said he’d make every politician across the country read Jacqueline Woodson’s Brown Girl  Dreaming. And he’d insist on filling grade K-12 classrooms with much more poetry.

Dreaming. And he’d insist on filling grade K-12 classrooms with much more poetry.

LitLife and LitWorld’s dynamo Pam Allyn said she’d require all members of Congress to send their children to public schools to ensure that they’re actually stake holders in whatever legislation is being considered.

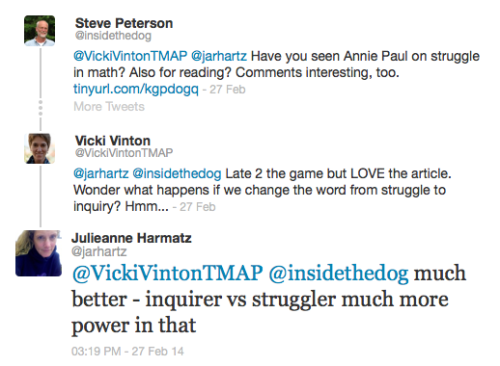

And recent NCTE President Ernest Morrell called for the elimination of all deficit language in schools, for students and teachers alike, which means no more labeling of children as strugglers and teachers as ineffective.

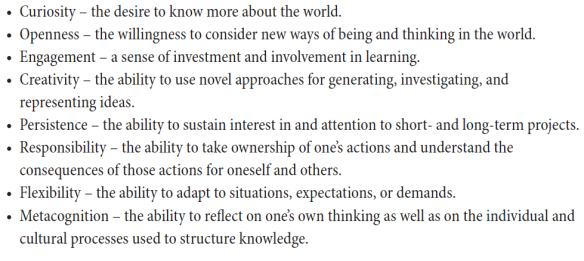

This process also led many of this year’s speakers to share new thoughts and ideas. Ellin Keene, for instance, shared her latest thinking about what’s involved in true student engagement, versus its evil twin, compliance. Her answer? Engagement requires the following four factors:

Intellectual urgency (or the need to know),

Emotional responses to ideas,

Perspective bending, and

Opportunities for aesthetic experiences

Tom Newkirk, on the other hand, helped me recognize something I knew but had never really articulated before: that we don’t read great nonfiction to learn information, but for the same reason we read any other kind of literature: to deepen our understanding of the human experience and, in the words of Kenneth Burke “to arouse and fulfill our desire” to connect. And my friends and colleagues from the Opal School, Matt Karlson, Susan Mackay and Mary Gage Davis, were on fire as they shared new ideas on the connection between beauty and social justice—and made their own impassioned plea to bring imagination, “the neglected stepchild of American education” back into classrooms.

I’m sure I’ll have much more to say about these ideas as time goes by, as they really got my mind churning. But for now, many thanks to NCTE for reminding me to always:

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as  unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as

unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as

So what would a truly rich task in literacy look like? For me, it seems to be a new way of talking about the kind of problem solving I often ask kids to do, which, in one way or another, involves thinking about what an author might be trying to show us or asking us to consider in a scene, a passage, a line, a whole text. Depending on the text, this might also be framed in a slightly more specific way, as I’ve been doing with one of my favorite finds of the year,

So what would a truly rich task in literacy look like? For me, it seems to be a new way of talking about the kind of problem solving I often ask kids to do, which, in one way or another, involves thinking about what an author might be trying to show us or asking us to consider in a scene, a passage, a line, a whole text. Depending on the text, this might also be framed in a slightly more specific way, as I’ve been doing with one of my favorite finds of the year,

Many of the practices he suggested were similar to those advised by

Many of the practices he suggested were similar to those advised by

Compared to the students who were circling A or D in the Anticipation Guides above, these students were involved in much higher order thinking as they used what they’d noticed to infer and developed hypotheses that might explain what caused the difference in the two pictures. They were constructing new understanding, at least a provisional one. And feeling a burning need to know, especially about the fate of the buildings, they eagerly dove into an article about the problems Venice faced with the kind of intellectual involvement that Charlotte Danielson speaks about.

Compared to the students who were circling A or D in the Anticipation Guides above, these students were involved in much higher order thinking as they used what they’d noticed to infer and developed hypotheses that might explain what caused the difference in the two pictures. They were constructing new understanding, at least a provisional one. And feeling a burning need to know, especially about the fate of the buildings, they eagerly dove into an article about the problems Venice faced with the kind of intellectual involvement that Charlotte Danielson speaks about. I’m aware, of course, that it may seem much easier to tap into students’ curiosity with a compelling image than with a complex text (which

I’m aware, of course, that it may seem much easier to tap into students’ curiosity with a compelling image than with a complex text (which

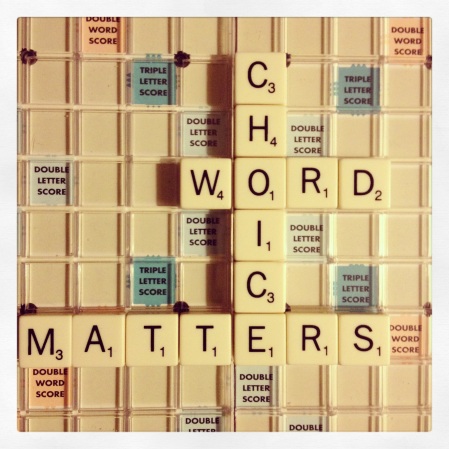

The title and lead picture of this week’s post comes by way of

The title and lead picture of this week’s post comes by way of  When it comes to reading, we might gather texts to choose a great read aloud to anchor a unit on a genre, author, topic or theme, or to create a text set. Coincidentally enough, this week’s “

When it comes to reading, we might gather texts to choose a great read aloud to anchor a unit on a genre, author, topic or theme, or to create a text set. Coincidentally enough, this week’s “ Studying texts in this way also helps teachers become more aware of how the writer of a chosen text uses specific details, imagery and patterns to explore ideas, which is how I interpret the Common Core’s reading standards on craft. As I shared in a

Studying texts in this way also helps teachers become more aware of how the writer of a chosen text uses specific details, imagery and patterns to explore ideas, which is how I interpret the Common Core’s reading standards on craft. As I shared in a  equivalent of the fifth step in Matt and Mary Alice’s planning process: Anticipating Issues and Possible Small Group Work. In looking closely at the textbook I shared last week, the teacher I worked with anticipated that her students might not catch the tiny but important word ‘in’, which explained the relationship between minerals and rocks. So we anticipated planning some small group lessons to gave students additional time to practice thinking about the relationship or connection between the key words of a text. With One Green Apple, on the other hand, I anticipated that not every student would be able to see the metaphoric connection between the green apple and the main character, Farah. And while those who couldn’t might be able to piggyback on the thinking of others, I anticipated needing to plan some

equivalent of the fifth step in Matt and Mary Alice’s planning process: Anticipating Issues and Possible Small Group Work. In looking closely at the textbook I shared last week, the teacher I worked with anticipated that her students might not catch the tiny but important word ‘in’, which explained the relationship between minerals and rocks. So we anticipated planning some small group lessons to gave students additional time to practice thinking about the relationship or connection between the key words of a text. With One Green Apple, on the other hand, I anticipated that not every student would be able to see the metaphoric connection between the green apple and the main character, Farah. And while those who couldn’t might be able to piggyback on the thinking of others, I anticipated needing to plan some

As Dorothy Barnhouse and I both noticed and discussed in

As Dorothy Barnhouse and I both noticed and discussed in  For Johnston, the key to learning isn’t explicit teacher modeling but student engagement. And from 2008 to 2010 he was involved in a research study that yielded compelling proof of that. As he shared in a recent blog post titled

For Johnston, the key to learning isn’t explicit teacher modeling but student engagement. And from 2008 to 2010 he was involved in a research study that yielded compelling proof of that. As he shared in a recent blog post titled  From the cover, they wondered what a name jar was, why the book was called that, who put the names in the jar and why, and was the girl putting something in or taking something out? With these questions in mind and their curiosity sparked, I started reading, pausing periodically to let them turn and talk and share out what they were thinking out.

From the cover, they wondered what a name jar was, why the book was called that, who put the names in the jar and why, and was the girl putting something in or taking something out? With these questions in mind and their curiosity sparked, I started reading, pausing periodically to let them turn and talk and share out what they were thinking out.

Watching those students talk and work, several of us found ourselves thinking about how different that sustained concentration was to the way we tend to talk about stamina and the need for children to build it. We talk as we’re preparing students for an endurance test, something that’s arduous and beyond their ability without weeks and weeks of training. The students in Reggio, however, hadn’t ‘built up stamina’; they were simply deeply engaged with what they were doing. And they were engaged not because the teacher had hooked them with something fun or diverting or offered them a reward, but because they were eager to wrap their minds around whatever problem the teacher had invited them to consider through either the arrangement of materials (in the case of the girl with the pomegranate) or an intriguing, provocative question (in the case of the negative number group).

Watching those students talk and work, several of us found ourselves thinking about how different that sustained concentration was to the way we tend to talk about stamina and the need for children to build it. We talk as we’re preparing students for an endurance test, something that’s arduous and beyond their ability without weeks and weeks of training. The students in Reggio, however, hadn’t ‘built up stamina’; they were simply deeply engaged with what they were doing. And they were engaged not because the teacher had hooked them with something fun or diverting or offered them a reward, but because they were eager to wrap their minds around whatever problem the teacher had invited them to consider through either the arrangement of materials (in the case of the girl with the pomegranate) or an intriguing, provocative question (in the case of the negative number group). Once again, my new eyes prompted me to question practices I took for granted—and not just about the dubious idea of putting up charts to impress evaluators. I thought of all those times I’ve seen students answer questions by spouting off the words on a chart without really understanding them. Those students can seemingly talk the talk, but not walk the walk. And this, in turn, begged another question: Have students really learned something if their hold on it is so tenuous that they need constant reminders? And if, as I suspect, the answer is no, won’t they learn better by having additional opportunities to discover and experience what those charts say readers do instead of relying on written reminders whose meaning they haven’t yet felt?

Once again, my new eyes prompted me to question practices I took for granted—and not just about the dubious idea of putting up charts to impress evaluators. I thought of all those times I’ve seen students answer questions by spouting off the words on a chart without really understanding them. Those students can seemingly talk the talk, but not walk the walk. And this, in turn, begged another question: Have students really learned something if their hold on it is so tenuous that they need constant reminders? And if, as I suspect, the answer is no, won’t they learn better by having additional opportunities to discover and experience what those charts say readers do instead of relying on written reminders whose meaning they haven’t yet felt?

As the school year finally begins to wind down here in New York City, a new term is the air: text dependent questions. I first encountered the term in the

As the school year finally begins to wind down here in New York City, a new term is the air: text dependent questions. I first encountered the term in the  These text dependent questions stand in contrast to some of the common kinds of questions often heard in classrooms, such as questions about students’ own feelings or experiences and questions related to strategies or skills, like “What’s the main idea?” I agree that these kinds of questions are problematic and should be used sparingly. The first kind can shift students’ attention away from the text to their own thoughts, while the second can turn the act of reading into a scavenger hunt, as I explored a few weeks ago in

These text dependent questions stand in contrast to some of the common kinds of questions often heard in classrooms, such as questions about students’ own feelings or experiences and questions related to strategies or skills, like “What’s the main idea?” I agree that these kinds of questions are problematic and should be used sparingly. The first kind can shift students’ attention away from the text to their own thoughts, while the second can turn the act of reading into a scavenger hunt, as I explored a few weeks ago in

But what if, instead, we taught students that every reader enters a text not knowing where it’s headed, and because of that they keep track of what they’re learning and what they’re confused or wondering about, knowing that they’ll figure out more as they both read forward and think backwards? This vision of what readers do acknowledges that reading is just as much a process of drafting and revising as writing is, with readers constantly questioning and developing their understanding of what an author is saying as they make their way through a text. And it supports the idea that readers are actively engaged and thinking about how the pieces of a text fit together, beginning with the very first line.

But what if, instead, we taught students that every reader enters a text not knowing where it’s headed, and because of that they keep track of what they’re learning and what they’re confused or wondering about, knowing that they’ll figure out more as they both read forward and think backwards? This vision of what readers do acknowledges that reading is just as much a process of drafting and revising as writing is, with readers constantly questioning and developing their understanding of what an author is saying as they make their way through a text. And it supports the idea that readers are actively engaged and thinking about how the pieces of a text fit together, beginning with the very first line.

Students who had noticed the title, might say that the narrator was a slave, which would help answer the first question and also raise a lot more, including how a slave got to be friends with white boys; where, exactly, was this taking place; how old is/was the narrator; and, as they read further on, how did he manage to get a book and was he allowed to take the bread or had he stolen it. Reading forward on the lookout for answers to these student-generated questions, the students would pick up clues that engaged them in considering the third text dependent question about how Douglass’s life as a slave differed from those of the boys. And those students who hadn’t caught the title could hold on to the question, made visible by the chart, until later on in the passage where they’d encounter more clues. And at that point they’d need to think backwards to revise whatever they’d made of the text so far in light of this realization.

Students who had noticed the title, might say that the narrator was a slave, which would help answer the first question and also raise a lot more, including how a slave got to be friends with white boys; where, exactly, was this taking place; how old is/was the narrator; and, as they read further on, how did he manage to get a book and was he allowed to take the bread or had he stolen it. Reading forward on the lookout for answers to these student-generated questions, the students would pick up clues that engaged them in considering the third text dependent question about how Douglass’s life as a slave differed from those of the boys. And those students who hadn’t caught the title could hold on to the question, made visible by the chart, until later on in the passage where they’d encounter more clues. And at that point they’d need to think backwards to revise whatever they’d made of the text so far in light of this realization.

As opinion writing made its way to lower schools, many teachers discovered the wonderful picture book

As opinion writing made its way to lower schools, many teachers discovered the wonderful picture book

While narrative procedures do not appear, as such, on the Common Core Standards, they are a kind of writing that informs or explains a process or procedure, which makes them a good vehicle for meeting the information writing standard. Unfortunately, though, for some students that means explaining how to make something like a peanut butter and jelly sandwich year after year after year. And so at some point I and a few intrigued teachers began rethinking procedural writing in middle school by introducing how-to essays and stories written in the second person, such as

While narrative procedures do not appear, as such, on the Common Core Standards, they are a kind of writing that informs or explains a process or procedure, which makes them a good vehicle for meeting the information writing standard. Unfortunately, though, for some students that means explaining how to make something like a peanut butter and jelly sandwich year after year after year. And so at some point I and a few intrigued teachers began rethinking procedural writing in middle school by introducing how-to essays and stories written in the second person, such as  The first is Chris Kanarick’s hilarious “How to Survive Shopping with Mom,” which appears in the wonderful anthology

The first is Chris Kanarick’s hilarious “How to Survive Shopping with Mom,” which appears in the wonderful anthology  And then there’s Dorsey Seignious’s incredibly moving “When You,” which appears in another great anthology for older students,

And then there’s Dorsey Seignious’s incredibly moving “When You,” which appears in another great anthology for older students,  Finally, in

Finally, in  Writers of forewards and appreciations explore the meaning a book held for them, while also summarizing and talking about elements such as characters and themes. They also usually include a memoir-ish vignette about reading the book for the first time and they frequently touch on the reasons why we read, as Michael Chabon does here in

Writers of forewards and appreciations explore the meaning a book held for them, while also summarizing and talking about elements such as characters and themes. They also usually include a memoir-ish vignette about reading the book for the first time and they frequently touch on the reasons why we read, as Michael Chabon does here in

To begin with, every single reader who responded was deeply engaged in thinking about what particular details might mean, both individually and in relationship to the whole. They considered the significance of the fortune cookie, the father’s comment about “all oyster and no pearl,” the billfold rising up “like a dark fish,” and the puzzling line that several mentioned, “There will be time enough for silence and rest.” Sometimes they had specific ideas about what those details might be revealing about character or even theme, and sometimes they weren’t sure what to do with them. But they all entered the text assuming that the details they encountered weren’t random but had been deliberately chosen by the author to convey something more than, say, the literal contents of a wallet. And as readers, their job was to attend to those details and to question and consider their meaning, which they did by wondering and brainstorming possibilities in a way that seemed less firm or emphatic than an inference or a prediction.

To begin with, every single reader who responded was deeply engaged in thinking about what particular details might mean, both individually and in relationship to the whole. They considered the significance of the fortune cookie, the father’s comment about “all oyster and no pearl,” the billfold rising up “like a dark fish,” and the puzzling line that several mentioned, “There will be time enough for silence and rest.” Sometimes they had specific ideas about what those details might be revealing about character or even theme, and sometimes they weren’t sure what to do with them. But they all entered the text assuming that the details they encountered weren’t random but had been deliberately chosen by the author to convey something more than, say, the literal contents of a wallet. And as readers, their job was to attend to those details and to question and consider their meaning, which they did by wondering and brainstorming possibilities in a way that seemed less firm or emphatic than an inference or a prediction. There were also none of the literal text-to-self connections we frequently hear in classrooms—that is, no stories about pick-pocketed wallets or aging fathers in Florida. Mostly readers connected with their previous experiences as readers. And the one reader who explicitly made a connection to his grandfather pushed and prodded and probed that connection, connecting it to other details and memories until it yielded an insight about the text.

There were also none of the literal text-to-self connections we frequently hear in classrooms—that is, no stories about pick-pocketed wallets or aging fathers in Florida. Mostly readers connected with their previous experiences as readers. And the one reader who explicitly made a connection to his grandfather pushed and prodded and probed that connection, connecting it to other details and memories until it yielded an insight about the text. It’s also worth noting that no reader made a definitive claim about ‘the theme’ of the story. Perhaps they would have if I’d asked them to; but at the risk of speaking for them, I think that, as readers, they didn’t feel a need to sum up and fit all they were thinking into a single statement—yet. They were, however, all circling ideas that we could call understandings or themes. One, for instance, was trying to “reconcile the complex notion that the father might be embarrassed but also delighted at the same time,” while others kept thinking about that fortune cookie, aware that the events of the story refuted its life-is-always-the-same-old-story message. One thought the story was “at least partly about” our society’s view of the elderly, while others considered what it might be saying about father and son relationships. And having that line about silence and rest brought to my attention by a few readers, I found myself thinking about mortality and death, which seems to hover over the story as yet another layer and lens for thinking about its ideas.

It’s also worth noting that no reader made a definitive claim about ‘the theme’ of the story. Perhaps they would have if I’d asked them to; but at the risk of speaking for them, I think that, as readers, they didn’t feel a need to sum up and fit all they were thinking into a single statement—yet. They were, however, all circling ideas that we could call understandings or themes. One, for instance, was trying to “reconcile the complex notion that the father might be embarrassed but also delighted at the same time,” while others kept thinking about that fortune cookie, aware that the events of the story refuted its life-is-always-the-same-old-story message. One thought the story was “at least partly about” our society’s view of the elderly, while others considered what it might be saying about father and son relationships. And having that line about silence and rest brought to my attention by a few readers, I found myself thinking about mortality and death, which seems to hover over the story as yet another layer and lens for thinking about its ideas.