Last week I got to hangout on Google with Fran McVeigh, Julieanne Harmatz Steve Peterson and Mary Lee Hahn to talk through the session we’ll be presenting together at this year’s NCTE conventional at National Harbor, just south of D.C. The talk was deep and rich and energizing, and it made me want to share a few details about that and other places I’ll be presenting over the next several months, where, as always, I’d relish the chance to meet blog readers in person.

Before jumping on the Bolt Bus to D.C., however, I’ll be heading half-way around the world to the city of Doha in Qatar. In addition to working for several days with teachers (and my Reggio-Emilia comrade, Katrina Theilmann) at the American School in Doha, I’ll be facilitating a two-day workshop on “Teaching the Process of Meaning Making in Reading,” as part of the NESA (Near East South Asia Council of Overseas Schools) Fall Training Institute, which will be held on November 7 and 8. I know it’s highly unlikely that I’ll run into any stateside blog readers there, but I’m hoping to touch base with a few overseas ones as well as reconnect to some of my other Reggio-Emilia trip colleagues as well.

Before jumping on the Bolt Bus to D.C., however, I’ll be heading half-way around the world to the city of Doha in Qatar. In addition to working for several days with teachers (and my Reggio-Emilia comrade, Katrina Theilmann) at the American School in Doha, I’ll be facilitating a two-day workshop on “Teaching the Process of Meaning Making in Reading,” as part of the NESA (Near East South Asia Council of Overseas Schools) Fall Training Institute, which will be held on November 7 and 8. I know it’s highly unlikely that I’ll run into any stateside blog readers there, but I’m hoping to touch base with a few overseas ones as well as reconnect to some of my other Reggio-Emilia trip colleagues as well.

Next up will be NCTE where I’ll be chairing the session that was mapped out in that Google Hangout last week on Friday November 21 at 4:15. Titled “It’s Not Just for the Kids: Stories of What Can Happen When Teachers Embrace Curiosity, Openness, Creativity and Wonder in the Teaching of Reading,” each presenter will share work they’ve done—some with students, some with teachers—that grew out of questions they wondered about and pursued with passion and curiosity. And I’ll be there to connect the pieces together and share the story of how we all discovered each other, from New York to  Ohio to Iowa to California, through the blogosphere.

Ohio to Iowa to California, through the blogosphere.

I’ll also be presenting the following day, November 22, again at 4:15 with two of my favorite people in the world, Mary Ehrenworth and Katherine Bomer, in a session called “Embracing Complexity: Helping Students (and Ourselves) Become More Complex Readers, Writers and Learners.” While we’re still ironing out the final details of that session, we’ll each share classroom stories and student work that show what can happen when we move away from more teacher-directed procedural ways of teaching to something more messy and complex.

After that I’ll be in Portland, Oregon, December 9 and 10, presenting a workshop for educators sponsored by the Portland Children’s Museum Center for Learning and the Opal School. Called “Extending Our Image of Children: New Possibilities for Readers,” Opal School teachers and I will share stories and ways in which we’ve invited children to enter texts as authentic readers. And I’ll also have the amazing opportunity to model some of the approaches I’ve developed in an Opal School classroom—though I imagine the kids will steal the show (as well they should).

After that I’ll be in Portland, Oregon, December 9 and 10, presenting a workshop for educators sponsored by the Portland Children’s Museum Center for Learning and the Opal School. Called “Extending Our Image of Children: New Possibilities for Readers,” Opal School teachers and I will share stories and ways in which we’ve invited children to enter texts as authentic readers. And I’ll also have the amazing opportunity to model some of the approaches I’ve developed in an Opal School classroom—though I imagine the kids will steal the show (as well they should).

And finally, after what I hope will be two balmy days in Los Angeles in January working with LAUSD’s wonderful Education Service Center South coaches and teachers, I’ll be heading north to wintery Toronto for the Reading for the Love of It Language Arts Conference on February 9 and 10, 2015. Along with other amazing presenters, such as Ruth Culham, Pat Johnson, Tanny McGregor and Linda Rief, I’ll be doing two sessions, one on “Helping Students and Ourselves Become Critical Thinkers and Insightful Readers,” which will focus on fiction and “What’s the Main Idea of the Main Idea: From Scavenger Hunting to Synthesizing in Nonfiction Texts.”

And finally, after what I hope will be two balmy days in Los Angeles in January working with LAUSD’s wonderful Education Service Center South coaches and teachers, I’ll be heading north to wintery Toronto for the Reading for the Love of It Language Arts Conference on February 9 and 10, 2015. Along with other amazing presenters, such as Ruth Culham, Pat Johnson, Tanny McGregor and Linda Rief, I’ll be doing two sessions, one on “Helping Students and Ourselves Become Critical Thinkers and Insightful Readers,” which will focus on fiction and “What’s the Main Idea of the Main Idea: From Scavenger Hunting to Synthesizing in Nonfiction Texts.”

So much to see, so much to plan for! Here’s hoping I get to see some of you, too!

As we head into June, much of my time seems devoted to tying up loose ends and reflecting back on the year. And with loose ends and reflection in my mind, I’d like to share four resources I discovered over the school year that I couldn’t seem to find a home for in another post.

As we head into June, much of my time seems devoted to tying up loose ends and reflecting back on the year. And with loose ends and reflection in my mind, I’d like to share four resources I discovered over the school year that I couldn’t seem to find a home for in another post. The book is about a girl named Ruby who, unlike her unique but self-absorbed parents (mom makes tiaras and dad creates topiaries), wants only to be normal. The class’s teacher wasn’t sure that her students would know what a tiara or a topiary was, let alone a glacier, and she also wondered if they’d get a book about a child who was embarrassed by her parents. She was game, though, to try it out and so we decided not to front-load any vocabulary but see how much the kids could figure out. This meant that many at first thought that the strange white object on the cover might be a package containing a pet. And while some thought that on the page below Ruby hoped that no one from school would see her because she was playing with dolls, others wondered if it was because she was didn’t want anyone seeing her parents, who had been shown on the page before dancing the tango through the topiaries in tiaras.

The book is about a girl named Ruby who, unlike her unique but self-absorbed parents (mom makes tiaras and dad creates topiaries), wants only to be normal. The class’s teacher wasn’t sure that her students would know what a tiara or a topiary was, let alone a glacier, and she also wondered if they’d get a book about a child who was embarrassed by her parents. She was game, though, to try it out and so we decided not to front-load any vocabulary but see how much the kids could figure out. This meant that many at first thought that the strange white object on the cover might be a package containing a pet. And while some thought that on the page below Ruby hoped that no one from school would see her because she was playing with dolls, others wondered if it was because she was didn’t want anyone seeing her parents, who had been shown on the page before dancing the tango through the topiaries in tiaras.

Finally, while I was at NCTE I snagged a copy of

Finally, while I was at NCTE I snagged a copy of

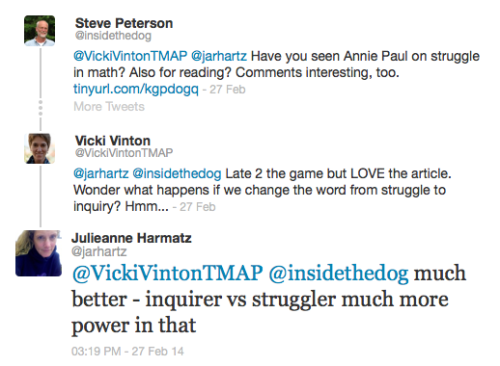

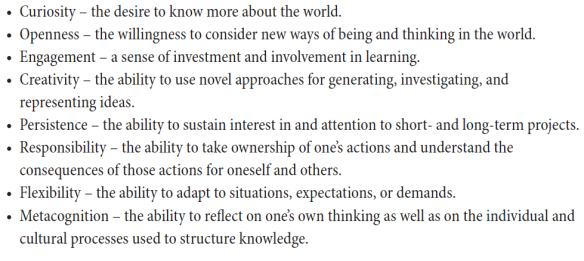

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as  unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as

unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as

While I couldn’t quite manage to get this out before the turkey was carved, I’d like to give my thanks this week to the amazing educators I had the privilege of hearing at last week’s

While I couldn’t quite manage to get this out before the turkey was carved, I’d like to give my thanks this week to the amazing educators I had the privilege of hearing at last week’s

And finally, in perhaps the most subversive talk, I saw middle school teacher and cartoonist

And finally, in perhaps the most subversive talk, I saw middle school teacher and cartoonist