One of the joys of writing a book—beyond simply finishing it—is getting feedback from readers. And one of the first reader comments I saw came from Rebekah O’Dell, the co-author with Allison Marchetti of the marvelous book Writing with Mentors and the website movingwriters.org, who tweeted this soon after the book came out:

Here, Rebekah highlighted a passage from Dynamic Teaching for Deeper Reading that I imagined might provoke the kind of spirited discourse and cognitive dissonance that Ellin Keene wrote about in her foreword. That’s because, in addition to the still ongoing battles between phonics and whole language and Common Core-style close reading and balanced literacy, there’s another war still underway between knowledge-based and more inquiry and problem-based approaches to reading.

The knowledge-based approach is rooted in a body of research that shows a connection between students’ prior knowledge and their reading comprehension. Based on that, knowledge advocates, like Doug Lemov, Daniel Willingham, E. D. Hirsch and the authors of the Common Core, argue that if prior knowledge helps students comprehend more, then teachers should focus on building up students’ store of knowledge.

The knowledge-based approach is rooted in a body of research that shows a connection between students’ prior knowledge and their reading comprehension. Based on that, knowledge advocates, like Doug Lemov, Daniel Willingham, E. D. Hirsch and the authors of the Common Core, argue that if prior knowledge helps students comprehend more, then teachers should focus on building up students’ store of knowledge.

On the one hand, there is some logic to this, but it raises lots of questions. First and foremost is who gets to choose what knowledge should be taught to whom and when. The Core Knowledge Foundation, for instance, offers a knowledge-based Language Arts Curriculum for grades Pre-K though five that many students schools across the country use—and to my mind at least, many of their choices seem strange.

Among other things, for example, first graders learn about Early World Civilizations, including Mesopotamia and Egypt, which, in New York State, is covered in 6th grade social studies. And during the unit they also learn about the world’s three monotheistic religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam—along with a slew of vocabulary words I doubt a first grader will have much use for in their daily lives.

Second graders, on the other hand, learn about the War of 1812, which I remember virtually nothing about. And fifth graders study the Reformation, which, in case you don’t remember, is, as the unit overview states, “the 16th-century religious and political upheaval that challenged the power of the Catholic Church and led to the creation of Protestantism.”

I have to believe I’m not the only one who thinks these choices are bizarre, if not indoctrinary. Why the Reformation instead of, say, the Underground Railroad, the 1960’s or the schism in Islam between Sunnis and Shiites? Why the War of 1812? And why is the one literature unit  at each grade focused only on abridged versions of ‘classics’? Fourth graders, for instance, read Treasure Island, while third graders listen to a read aloud of Kenneth Grahame’s over 100-year-old The Wind in the Willows—the story about the dissolute son of a British aristocrat (who just happens to be a toad) who learns how to become a responsible lord through the help of his friends Mole, Rat and Badger. Why that rather than, say, Because of Winn-Dixie? or The One and Only Ivan? Because there are so many allusions to The Wind in the Willows in the world? I don’t think so. But I have recently spotted several headlines that allude to more contemporary books, like this one from The Washington Post that refers to Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day by Judith Viorst:

at each grade focused only on abridged versions of ‘classics’? Fourth graders, for instance, read Treasure Island, while third graders listen to a read aloud of Kenneth Grahame’s over 100-year-old The Wind in the Willows—the story about the dissolute son of a British aristocrat (who just happens to be a toad) who learns how to become a responsible lord through the help of his friends Mole, Rat and Badger. Why that rather than, say, Because of Winn-Dixie? or The One and Only Ivan? Because there are so many allusions to The Wind in the Willows in the world? I don’t think so. But I have recently spotted several headlines that allude to more contemporary books, like this one from The Washington Post that refers to Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day by Judith Viorst:

and this one from the Los Angeles Review of Books, that compares and contrasts the villain in Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events books Count Olaf with Donald Trump (e.g., they are both liars):

I’m certainly not suggesting that we make all children read these particular books rather than other particular books, since doing so inevitably involves bias. Nor am I saying that having a rich body of knowledge isn’t important. But the fact is that, as I write in the book, we simply can’t teach students what’s behind every reference or allusion they might encounter, nor every vocabulary word they might come across.There’s simply too much information in the world—and the volume of knowledge being generated is growing exponentially at an astounding speed, as can been seen in these facts from the video Did You Know? Shift Happens:

With these facts in mind, advocates, such as Linda Darling-Hammond, Michael Fullan, Will Richardson and (no surprise here) yours truly, argue that rather than learning reams of content knowledge, what students in the 21st century need are opportunities to construct and apply knowledge, think critically and creatively, solve problems, and learn how to learn—which knowledge-based proponents have been known to say is simply a “romantic notion.”

Just this week, though, Education Week put out a special report called Schools and the Future of Work: What Will Our Students Need to Know? And in articles with titles like “The Future of Work Is Uncertain, Schools Should Worry Now,” “Stop Teaching Students What to Think. Teach Them How to Think,” and “Learning How to Learn Could Be a Student’s Most Valuable Skill,” the report definitely seems to the constructivist/inquiry/problem-based side of the debate.

Just this week, though, Education Week put out a special report called Schools and the Future of Work: What Will Our Students Need to Know? And in articles with titles like “The Future of Work Is Uncertain, Schools Should Worry Now,” “Stop Teaching Students What to Think. Teach Them How to Think,” and “Learning How to Learn Could Be a Student’s Most Valuable Skill,” the report definitely seems to the constructivist/inquiry/problem-based side of the debate.

But here’s the thing: As Alfie Kohn, another learning-to-think proponent, writes in “What Does It Mean to Be Well-Educated?” “No one thinks in a vacuum . . . A classroom whose primary focus is described by phrases such as deep understanding, critical thinking, creativity, and the construction of meaning isn’t one devoid of facts. But it’s purposes go well beyond the transmission of a long list of dates, definitions, and other details.”

Consider, for a moment, the fifth graders I wrote about in my last post who had no idea of what a refugee was or a settlement camp before they read Katherine Applegate’s Home of the Brave. Rather than being taught those words and told about the crisis in Sudan, they figured those things out, and along the way learned many things, not only about the plight of refugees and the tragedy that occurred (and is still occurring) in Sudan. They learned how to see their own country through the eyes of someone quite different; how to discover our shared humanity with others whose lives are nothing like ours; how reading closely and attentively empowered them as readers and thinkers; and how verb tense and punctuation actually matter. And they also learned the deep satisfaction and pleasure that comes from “the curiosity to ask big questions [and] the drive to understand those questions deeply,” which one of the contributors to EdWeek’s report says are traits that are urgently needed in our every changing world.

So why focus so much on content knowledge, when students can gain so much more?

despite the fact that it was cheaper than McDonald’s Quarter Pounder and preferred in blind taste tests. Turns out the problem was that customers believed they were getting more beef for their money at McDonald’s, because they’d reasoned that one-fourth was greater than one-third since four was larger than three.

despite the fact that it was cheaper than McDonald’s Quarter Pounder and preferred in blind taste tests. Turns out the problem was that customers believed they were getting more beef for their money at McDonald’s, because they’d reasoned that one-fourth was greater than one-third since four was larger than three. i couldnt believe it the door opened in the middle of math class and the principal pushed this older raggedy kid in mrs cordell said boys and girls we have a new student in our class starting today his name is rufus fry now i know all of you will help make rufus feel welcome wont you someone giggled good rufus say hello to your new classmates please he didnt smile or wave or anything he just looked down and said real quiet hi a couple of girls thought he was cute because they said hi rufus why dont you sit next to kenny and he can help you catch up with what were doings mrs cordel said

i couldnt believe it the door opened in the middle of math class and the principal pushed this older raggedy kid in mrs cordell said boys and girls we have a new student in our class starting today his name is rufus fry now i know all of you will help make rufus feel welcome wont you someone giggled good rufus say hello to your new classmates please he didnt smile or wave or anything he just looked down and said real quiet hi a couple of girls thought he was cute because they said hi rufus why dont you sit next to kenny and he can help you catch up with what were doings mrs cordel said

Like

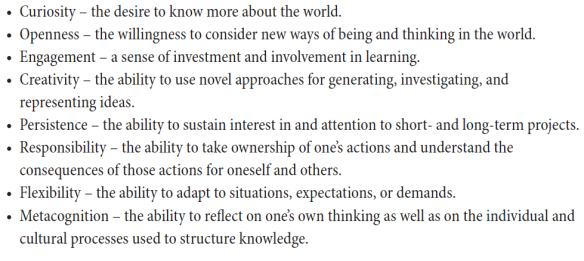

Like  school students care far more about achieving good grades than they do about learning. This is truly unfortunate because the thing about learning and achievement is this: If we focus on deeper learning, achievement tends to happen as a natural by-product. So why would we choose the word achievement when learning supports application and retention and increases the likelihood of achievement?

school students care far more about achieving good grades than they do about learning. This is truly unfortunate because the thing about learning and achievement is this: If we focus on deeper learning, achievement tends to happen as a natural by-product. So why would we choose the word achievement when learning supports application and retention and increases the likelihood of achievement?

often leads many to gravitate to programs that promise things, such as alignment with the Standards, increased student achievement, research-proven practices or ease of implementation. Every resource, in turn, comes with its own prescribed practices, whether it’s lists of text-dependent questions to ask (along with the answers to look for), scripts of mini-lessons to follow or protocols to use for instructional approaches like reciprocal or guided reading.

often leads many to gravitate to programs that promise things, such as alignment with the Standards, increased student achievement, research-proven practices or ease of implementation. Every resource, in turn, comes with its own prescribed practices, whether it’s lists of text-dependent questions to ask (along with the answers to look for), scripts of mini-lessons to follow or protocols to use for instructional approaches like reciprocal or guided reading.

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as  unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as

unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as