As the New York Times reported the other week, our new Schools Chancellor Carmen Farina recently gave a big endorsement to balanced literacy, which had been cast aside in many city schools after the previous administration embraced packaged reading programs, such as Pearson ReadyGen, Scholastic Codex and Core Knowledge, that were supposedly Common Core aligned. Many of these programs’ claims have since been called into question, but it’s Carmen Farina’s words that seem to have ushered us into a new stage in the reading wars. And from where I sit it’s gotten kind of ugly.

An op-ed piece in yesterday’s New York Times, for instance, called balanced literacy “an especially irresponsible approach,” while a commentary appearing in the Thomas B. Fordham Institute’s blog “Flypaper” called it a “hoax” and likened it to “the judo-like  practice of using terms that appeal to an audience as fig leaves for practices that same audience would find repugnant.” And over at “Used Books in Class,” my friend, colleague and fellow blogger Colette Bennett takes a look at another “Flypaper” writer who’s “recast the phrase ‘balanced literacy’ in mythological terms, as a hydra,” coming to get us. That’s a lot of virulent language for a pedagogical term.

practice of using terms that appeal to an audience as fig leaves for practices that same audience would find repugnant.” And over at “Used Books in Class,” my friend, colleague and fellow blogger Colette Bennett takes a look at another “Flypaper” writer who’s “recast the phrase ‘balanced literacy’ in mythological terms, as a hydra,” coming to get us. That’s a lot of virulent language for a pedagogical term.

What’s interesting to me, though, is that the New York Times article on Farina’s endorsement begins with an example of balanced literacy in action in a classroom, which is described as follows:

“[The teacher] took her perch in front of a class of restless fourth graders and began reciting the beginning of a book about sharks. But a few sentences in, [she] shifted course. She pushed her students to assume the role of teacher, and she became a mediator, helping guide conversations as the children worked with one another to define words like ‘buoyant’ and identify the book’s structure.”

And here’s an excerpt from “What Does a Good Common Core Lesson Look Like?” a story that appeared on NPR’s education blog, which also includes a classroom anecdote. The NPR piece looks at a ninth grade class that’s beginning to read Karen Russell’s short story “St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves,” which I wrote about earlier. This time, however, we’re told that we’re seeing close reading in action, not balanced literacy:

“First the teacher reads an excerpt of the story aloud . . . Then, students turn to individual close reading. They are told to reread sections and draw boxes around unfamiliar words [and] . . . after they have gotten to know the story well, students pair up to tease out the meaning of words like lycanthropic, couth and kempt.”

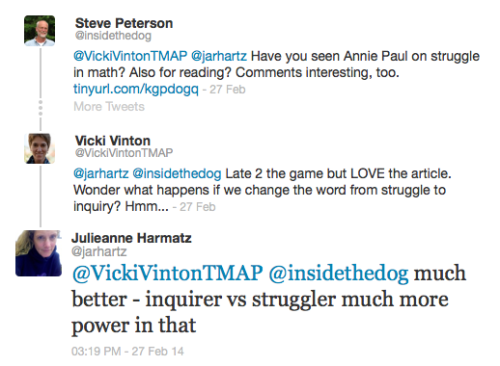

I hope I’m not the only one out there who thinks that, in all the really important ways, these two anecdotes are just alike. In the words of the ninth grade teacher quoted by NPR, both teachers are trying to “create content where there is a productive struggle… where all students are being asked to work toward the same target as everyone else” rather than “mak[ing] sure they see everything that’s cool about the text.”

I hope I’m not the only one out there who thinks that, in all the really important ways, these two anecdotes are just alike. In the words of the ninth grade teacher quoted by NPR, both teachers are trying to “create content where there is a productive struggle… where all students are being asked to work toward the same target as everyone else” rather than “mak[ing] sure they see everything that’s cool about the text.”

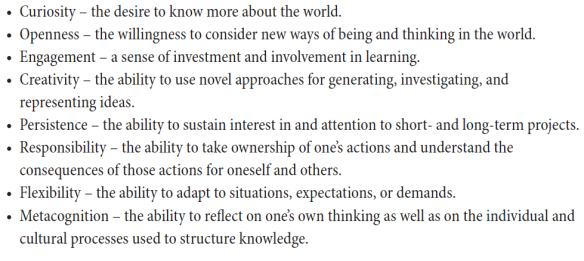

Of course I have some questions about whether that struggle should all be spent on vocabulary words instead of a text’s deeper meaning. And I would never begin the class as the ninth grade teacher does by discussing the standards with the students since I think the standards are for us, not for them. But the point I want to make here is that balanced literacy is an instructional structure, just as close reading is (or has become). And while I personally love balanced literacy because giving students a combination of whole class, small group and independent experiences just makes sense to me, what’s really important is not what structure a teacher uses, but how he or she uses it to help students read meaningfully and deeply. And that reminds me of a quote I shared a while ago from the authors of the great book Making Thinking Visible:

“Rather than concerning ourselves with levels among different types of thinking, we would do better to focus our attention on the levels of quality within a single type of thinking. For instance, one can describe at a very high and detailed level or at a superficial level. Likewise . . . analysis can be deep and penetrating or deal with only a few readily apparent features.”

I think the same is true about teaching approaches and structures: We’d do better to focus on the quality and depth that’s brought to a structure—i.e., what kind of thinking are we asking of students within whatever structure we use—rather than get caught up fighting over which one is better, knowing that a teacher who really listens to students, reflects on her practice and is a critical thinker and learner herself can make almost anything work.

And now that that’s off my chest, I want to share something else: I’m working on a new book on reading that I plan to finish by the end of the year. That doesn’t mean I’m bowing out of blogging, if for no other reason than writing a blog post is so much easier than writing a book. And I love the immediacy of it and the connection with other teachers and readers. But while I may be posting less frequently, I’ll still be trying to wrap my mind in words that speak to the things we all care about.

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as  unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as

unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as

When it comes to nonfiction, one thing seems clear: The exemplars tend to present information in far more varied and indirect ways than many a classroom’s standard fare. They mix-up modes, moving back and forth between narrative, exposition, description and persuasion, and they use the kind of literary techniques and devices more often associated with fiction and even poetry. In addition—or perhaps because—of all that, many of the texts defy the strategies we frequently offer students, such as scanning and skimming, identifying keywords, using text features to predict the content and, when it comes to vocabulary, thinking about prefixes, suffixes and roots and looking for context clues. This was certainly true of the text I decided to use for the workshop, “Gravity in Reverse: The Tale of Albert Einstein’s ‘Greatest Blunder'” by

When it comes to nonfiction, one thing seems clear: The exemplars tend to present information in far more varied and indirect ways than many a classroom’s standard fare. They mix-up modes, moving back and forth between narrative, exposition, description and persuasion, and they use the kind of literary techniques and devices more often associated with fiction and even poetry. In addition—or perhaps because—of all that, many of the texts defy the strategies we frequently offer students, such as scanning and skimming, identifying keywords, using text features to predict the content and, when it comes to vocabulary, thinking about prefixes, suffixes and roots and looking for context clues. This was certainly true of the text I decided to use for the workshop, “Gravity in Reverse: The Tale of Albert Einstein’s ‘Greatest Blunder'” by

“Negative gravity”, theorist, model, and “thought experiment,” on the other hand, were all words or phrases that the non-science teachers among us (including me) had to really think about. How, we wondered, did a theorist differ from an experimenter and how did that affect the scientific method? What did a ‘model’ in this context look like? And if “negative gravity” was the “mysterious and universal pressure that pervades all space,” where did it come from? How did it operate? And what did it have to do with Einstein?

“Negative gravity”, theorist, model, and “thought experiment,” on the other hand, were all words or phrases that the non-science teachers among us (including me) had to really think about. How, we wondered, did a theorist differ from an experimenter and how did that affect the scientific method? What did a ‘model’ in this context look like? And if “negative gravity” was the “mysterious and universal pressure that pervades all space,” where did it come from? How did it operate? And what did it have to do with Einstein?