This past week I had the opportunity to speak to New York City high school principals about writing. And as I did a while ago when I looked at how colleges view close reading, I decided to do a bit of research into what colleges were actually looking for in writing for my presentation. As happened then, when I found a significant difference between what colleges expect students to do as close readers and the often formulaic “three goes” at a text with text-dependent questions approach that I see in many schools, I discovered some significant gaps between how we teach writing—especially argument—and what colleges are looking for. And these gaps have enough implications for lower and middle school, as well as high school, that I thought I’d share what I found.

Here, for instance, are some timely tweets I discovered in a blog post written by a Canadian high school teacher title “Are We Teaching Students to Be Good Writers?” He’d attended a presentation by a college professor on the gaps between high school and college writing, and as part of the presentation, the professor shared a survey he gave to this third year college students, asking them what they wished they’d learned about writing in high school that would have better prepared them for college. And many of his students had this to say:

I wish I could say things were different in the States, but we, too, seem to spend a lot of time teaching students how to organize and structure their writing without spending equal, if not more, time in teaching them how to develop ideas in the first place. And from about third grade right up to twelfth, much of the teaching around organization and structure is focused  on the five-paragraph essay, where some students are taught not only how many paragraphs their essays should have but how many sentences each of those paragraphs should contain as well as the content of each.

on the five-paragraph essay, where some students are taught not only how many paragraphs their essays should have but how many sentences each of those paragraphs should contain as well as the content of each.

For the record, you should know that I’ve helped teachers teach the five paragraph essay myself. And while I do see that it can be a useful strategy for some students some of the time, we need to be aware that most college professors hate it—so much so that many explicitly un-teach it in freshman composition classes. According to the authors of Writing Analytically, a book that’s used in many of those college freshman writing classes, the five-paragaph essay commits the following offenses:

“It’s rigid, arbitrary and mechanical scheme values structure over just about everything, especially in-depth thinking . . . [and it’s] form runs counter to virtually all of the values and attitudes that students need to grow as writers and thinkers—such as a respect for complexity, tolerance of uncertainty and the willingness to test and complicate rather than just assert ideas.”

The thesis statement, too, which seems custom-made to assert versus test and complicate, gets a beating by many college professors, too. In his article for The Chronicle of Higher Education “Let’s End Thesis Tyranny,” for instance, Bruce Ballenger writes that “Rather than opening doors to thought, the thesis quickly closes them . . . [because] the habit of rushing to judgment short-circuits genuine academic inquiry.”

This all seems to suggest that even with the Common Core Standards’ focus on college and career readiness, we might not be doing such a great job at preparing students for  college writing. To close that gap, though, we need a clearer vision of what colleges do expect, and coincidentally—or serendipitously—enough, Grant Wiggin’s shared one of his college freshman son’s writing assignments in his recent blog post on argument, which does just that.

college writing. To close that gap, though, we need a clearer vision of what colleges do expect, and coincidentally—or serendipitously—enough, Grant Wiggin’s shared one of his college freshman son’s writing assignments in his recent blog post on argument, which does just that.

If you click through here you’ll see that the professor gives a brief summary of the assignment, which he/she calls a “Conversation Essay”. Then he/she provides some tips on college writing that are meant “to dispel some common and often paralyzing misconceptions about the nature of academic debate itself.” In particular, the professor targets what he/she calls an “ineffective” model for college writing: the “combat model.” That model, the professor writes,

“. . . suggests that academic debate consists of experts trying to tear down each other’s theories in the hope of proving that their own theory is actually correct. It suggests an aggressive approach and a battle zone in which people ‘advance’ arguments, ‘attack’ each other’s claim’s, and ‘stake out’ and ‘defend’ their own positions.”

Instead the professor is looking for an essay in which the writer inquires into and explores a problem, a question or one or more texts, with the goal of adding his or her own unique perspective and ideas to the the ongoing conversation about that problem, question or text. I think that means that whatever claims the writer makes need to be an outgrowth of his or her exploration, not what leads and determines the whole focus of the essays. And this vision of an essay seems quite close to what writer Alan Lightman says he was looking for in the essays he read as editor of The Best American Essays of 2000. There in the introduction, he writes:

“For me, the ideal essay is not an assignment, to be dispatched efficiently and intelligently, but an exploration, a questioning, an introspection . . . I want to see a mind at work, imagining, spinning, struggling to understand. If the essayist has all the answers, then he isn’t struggling to grasp, and I won’t either.”

In my next post, I’ll share some of the ideas and practices I explored with the principals last week, including the use of low-risk writing to help students take on that more exploratory stance and of mentor texts to give them both a vision and some choices about how their writing could look like based on what they have to say. But for now I want to offer one more reason why we might want to reconsider giving students a one-size-fits  all structure for academic writing. As I wrote about earlier, when we offer students scaffolds, we often inadvertently deprive them of something—in this case, the opportunity to engage and wrestle with one of the big concepts in reading and writing: how form informs content and how content can shape form.

all structure for academic writing. As I wrote about earlier, when we offer students scaffolds, we often inadvertently deprive them of something—in this case, the opportunity to engage and wrestle with one of the big concepts in reading and writing: how form informs content and how content can shape form.

This concept is what lies underneath the Common Core’s Craft and Structure Standards in reading, and by inviting students to think about what form might best suit and convey what they’re trying to say, we’d helped them become more aware of the purposefulness of a writer’s choice of structure. And in that way, too, they’d reap what Bird by Bird author Anne Lamott says is the big reward of writing: “Becoming a better writer is going to help you become a better reader, and that is the real payoff.” It will also ensure that students won’t have to un-learn what we’ve taught them once they get to college.

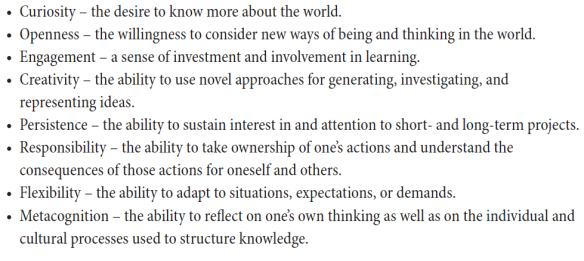

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as  unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as

unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as