I know many teachers and students around the country are already back in their classrooms, but for the third year I’d like to mark what here in New York City is the start of the school year by sharing some of the incredibly inspiring and thoughtful comments that educators have left on this blog over the last twelve months. Those months have been marked with ongoing conflict about the Common Core Standards, the corporatization of public education, standardized testing and certain literacy practices. Yet, if the comments below are any indication, it’s also been a year in which teachers have increasingly found their voices and are using them to speak out with passion, knowledge, and the conviction that comes from experience about what students—and they, themselves—need in order to be successful. And if I see a trend in this year’s comments, one of the things teachers are speaking out about is the need for a vision of education that’s not straight and simple, but messy and complex.

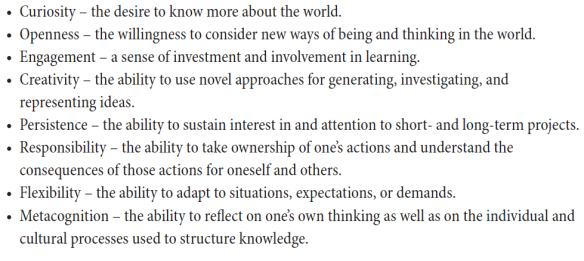

As happened before, it’s been quite a challenge to choose a handful of comments from the nearly two hundred I received. So if you find yourself hungry for more, you can scroll down and click on the comment bubble that appears to the right of each blog post’s title—and/or go to each responder’s blog by clicking on their name. You can also see the post they’re responding to by clicking on the image that goes with the comment. And for those of you who would love to hear and meet other bloggers and To Make a Prairie readers in person, I’ll be chairing a session at NCTE this year with Mary Lee Hahn, Julieanne Harmatz, Fran McVeigh and Steve Peterson called “It’s Not Just for the Kids: Stories of What Can Happen When Teachers Embrace Curiosity, Openness, Creativity and Wonder in the Teaching of Reading.”

And now, without any more ado and in no particular order, are some words to hold on to as we enter another year that I hope will be exciting for all:

“ Yes, it should be about the complexity of thought for our students. This is what they will carry with them into college and career—not a Lexile level. Spending time with a text and analyzing it through all those lenses to get the big picture should be our goal. I think many teachers are stuck on the standards, which to my mind is the old way of teaching. They want to create assessments for standards that they can easily grade and check off as ‘done’. We need to step back and think about how to teach our students to delve into a book and use multiple ways to explore the text, to come up with big ideas and original thinking. It begins with teaching them to love books and reading. We need to expose them to many kinds of texts with lots of opportunities to talk and write about what they’ve read. Not teach a skill, provide a worksheet, give an assessment and call it ‘done’. Annabel Hurlburt

Yes, it should be about the complexity of thought for our students. This is what they will carry with them into college and career—not a Lexile level. Spending time with a text and analyzing it through all those lenses to get the big picture should be our goal. I think many teachers are stuck on the standards, which to my mind is the old way of teaching. They want to create assessments for standards that they can easily grade and check off as ‘done’. We need to step back and think about how to teach our students to delve into a book and use multiple ways to explore the text, to come up with big ideas and original thinking. It begins with teaching them to love books and reading. We need to expose them to many kinds of texts with lots of opportunities to talk and write about what they’ve read. Not teach a skill, provide a worksheet, give an assessment and call it ‘done’. Annabel Hurlburt

“I too wrestle with how much to scaffold for students, and for adult learners and for how long. It seems the sooner we can remove the scaffold, the better. Sending learners off to inquire and grow their theories and ideas on their own, and to find their own answers is certainly always the goal—independence! . . . Seems that teaching students and adults as well to ask the big questions is also important, letting us grapple with new concepts and ideas grows us as learners. Less scaffolding supports this type of inquiry.” Daywells

“I too wrestle with how much to scaffold for students, and for adult learners and for how long. It seems the sooner we can remove the scaffold, the better. Sending learners off to inquire and grow their theories and ideas on their own, and to find their own answers is certainly always the goal—independence! . . . Seems that teaching students and adults as well to ask the big questions is also important, letting us grapple with new concepts and ideas grows us as learners. Less scaffolding supports this type of inquiry.” Daywells

“Another subtle nuance to a word is when we refer to schools as ‘buildings.’ A school is much more holy than that, because that’s where learning happens that shapes the future of the world. We don’t call houses of worship ‘building.’ We call them by their true names: church, synagogue, temple, mosque. These indicate that something spiritual is happening in them. When we call school a building, unless we’re talking about the physical plan, we’re helping them in the battle in lowering the value in what we do. These word choices seep into our daily work and shape our daily work into something we don’t want it to be!” Tom Marshall

“Another subtle nuance to a word is when we refer to schools as ‘buildings.’ A school is much more holy than that, because that’s where learning happens that shapes the future of the world. We don’t call houses of worship ‘building.’ We call them by their true names: church, synagogue, temple, mosque. These indicate that something spiritual is happening in them. When we call school a building, unless we’re talking about the physical plan, we’re helping them in the battle in lowering the value in what we do. These word choices seep into our daily work and shape our daily work into something we don’t want it to be!” Tom Marshall

“A point that stood out especially is that the inquiry process is not straight and easy. It is messy, and so we must let our students safely enter the muck. It can be difficult to know how much to intervene, especially when students seem to be veering far off course. The questioning you adapted from Jeff Wilhelm’s book seemed like a nice way to gently guide students toward considering more details before drawing conclusions, thus allowing them to arrive to more logical conclusions on their own. Anna Gratz Cockerille

messy, and so we must let our students safely enter the muck. It can be difficult to know how much to intervene, especially when students seem to be veering far off course. The questioning you adapted from Jeff Wilhelm’s book seemed like a nice way to gently guide students toward considering more details before drawing conclusions, thus allowing them to arrive to more logical conclusions on their own. Anna Gratz Cockerille

“I would add that a culture of looking at many viewpoints from the earliest ages can add to the abilities of students when they arrive at the more sophisticated levels like you’ve shared. Even kindergarten students can begin to look at other points of view through mentor text stories and through problem solving in their classroom communities when students bring their own experiences into conversations. Part of this means that teachers must be open to NOT asking for the ‘one right answer,’ [and instead] inviting possibilities.” Linda Baie

“I would add that a culture of looking at many viewpoints from the earliest ages can add to the abilities of students when they arrive at the more sophisticated levels like you’ve shared. Even kindergarten students can begin to look at other points of view through mentor text stories and through problem solving in their classroom communities when students bring their own experiences into conversations. Part of this means that teachers must be open to NOT asking for the ‘one right answer,’ [and instead] inviting possibilities.” Linda Baie

“‘Trainings’ operate with a limited vision of the competence and capabilities of teachers—and, in turn, support a model of education that operates with a limited vision of the competence and capabilities of children. Standing against that tendency means living in the tension between people desperately seeking simple answers to complicated questions and messy lived experience. I think that [the Opal School has] been siding with keeping it complicated, which seems to have the combined effect of deeply connecting with the learning of the educators who find us and limiting the number of people who do so. A real paradox! Matt Karlsen

“‘Trainings’ operate with a limited vision of the competence and capabilities of teachers—and, in turn, support a model of education that operates with a limited vision of the competence and capabilities of children. Standing against that tendency means living in the tension between people desperately seeking simple answers to complicated questions and messy lived experience. I think that [the Opal School has] been siding with keeping it complicated, which seems to have the combined effect of deeply connecting with the learning of the educators who find us and limiting the number of people who do so. A real paradox! Matt Karlsen

And with these words in mind, let’s get messy! And here’s hoping that I get a chance to see some of you in D.C. this November!

As we head into June, much of my time seems devoted to tying up loose ends and reflecting back on the year. And with loose ends and reflection in my mind, I’d like to share four resources I discovered over the school year that I couldn’t seem to find a home for in another post.

As we head into June, much of my time seems devoted to tying up loose ends and reflecting back on the year. And with loose ends and reflection in my mind, I’d like to share four resources I discovered over the school year that I couldn’t seem to find a home for in another post. The book is about a girl named Ruby who, unlike her unique but self-absorbed parents (mom makes tiaras and dad creates topiaries), wants only to be normal. The class’s teacher wasn’t sure that her students would know what a tiara or a topiary was, let alone a glacier, and she also wondered if they’d get a book about a child who was embarrassed by her parents. She was game, though, to try it out and so we decided not to front-load any vocabulary but see how much the kids could figure out. This meant that many at first thought that the strange white object on the cover might be a package containing a pet. And while some thought that on the page below Ruby hoped that no one from school would see her because she was playing with dolls, others wondered if it was because she was didn’t want anyone seeing her parents, who had been shown on the page before dancing the tango through the topiaries in tiaras.

The book is about a girl named Ruby who, unlike her unique but self-absorbed parents (mom makes tiaras and dad creates topiaries), wants only to be normal. The class’s teacher wasn’t sure that her students would know what a tiara or a topiary was, let alone a glacier, and she also wondered if they’d get a book about a child who was embarrassed by her parents. She was game, though, to try it out and so we decided not to front-load any vocabulary but see how much the kids could figure out. This meant that many at first thought that the strange white object on the cover might be a package containing a pet. And while some thought that on the page below Ruby hoped that no one from school would see her because she was playing with dolls, others wondered if it was because she was didn’t want anyone seeing her parents, who had been shown on the page before dancing the tango through the topiaries in tiaras.

Finally, while I was at NCTE I snagged a copy of

Finally, while I was at NCTE I snagged a copy of

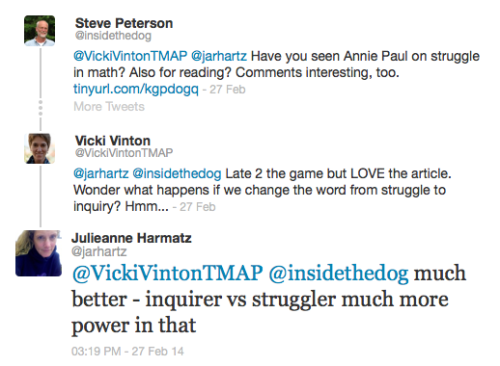

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as  unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as

unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as

While I’m a firm believer that poetry should be read throughout the year, I fear I tend to wait until April, when it’s National Poetry month, to write about it—just as many a teacher waits until then to dust off the poetry books. This is a shame, if not a crime, as is the fact that too many Common Core interpretations have all but squeezed poetry out of the curriculum or relegated it to a handful of lessons to tick off Reading Literature Standards 4 and 5.

While I’m a firm believer that poetry should be read throughout the year, I fear I tend to wait until April, when it’s National Poetry month, to write about it—just as many a teacher waits until then to dust off the poetry books. This is a shame, if not a crime, as is the fact that too many Common Core interpretations have all but squeezed poetry out of the curriculum or relegated it to a handful of lessons to tick off Reading Literature Standards 4 and 5. with the question “What does a poem do for a reader?” in mind, we get closer to Dylan Thomas as students start seeing that poems can make us smile or feel sad or see ordinary things in extraordinary ways. Once kids start feeling poems this way, it’s often fun to bring in quotes by poets like Dylan Thomas, which can affirm what students are experiencing and offer new ways of thinking about how a poem affects them—as in, considering which poems make your toe nails twinkle. For younger students I love using quotes from

with the question “What does a poem do for a reader?” in mind, we get closer to Dylan Thomas as students start seeing that poems can make us smile or feel sad or see ordinary things in extraordinary ways. Once kids start feeling poems this way, it’s often fun to bring in quotes by poets like Dylan Thomas, which can affirm what students are experiencing and offer new ways of thinking about how a poem affects them—as in, considering which poems make your toe nails twinkle. For younger students I love using quotes from  And this poem by

And this poem by  Many students can readily see that the poem on the card is broader and more general—even, we might say, generic—and it more or less hits one emotional note. Cofer’s poem, on the other hand, is highly specific. She writes about a particular mother who we can picture and hear and who is much more complicated than the every mom of the card. Because Cofer’s mother is so complicated, she and the poem seem more real to me than the ‘always’ mom of the card. And while my mom never wore an amulet or lived in a second-floor walk-up, the poem gets me thinking about all the complicated and confusing messages she sent me through the way she put on her lipstick or clutched my white-gloved hand in hers as we hurried through Grand Central Station.

Many students can readily see that the poem on the card is broader and more general—even, we might say, generic—and it more or less hits one emotional note. Cofer’s poem, on the other hand, is highly specific. She writes about a particular mother who we can picture and hear and who is much more complicated than the every mom of the card. Because Cofer’s mother is so complicated, she and the poem seem more real to me than the ‘always’ mom of the card. And while my mom never wore an amulet or lived in a second-floor walk-up, the poem gets me thinking about all the complicated and confusing messages she sent me through the way she put on her lipstick or clutched my white-gloved hand in hers as we hurried through Grand Central Station. students pick up whiffs of different feelings arising from different lines. In this poem, for instance, many students pick up fear, which they feel in various lines, though some also feel safety or relief in the last few lines or a sense of the daughter’s pride in the line about the “gypsy queen.”

students pick up whiffs of different feelings arising from different lines. In this poem, for instance, many students pick up fear, which they feel in various lines, though some also feel safety or relief in the last few lines or a sense of the daughter’s pride in the line about the “gypsy queen.”