As happened last year, many of the teachers, administrators and parents who left feedback on last month’s English Language Arts test at testingtalk.org pointed to what they felt were questions that focused on minutiae which, as Brooklyn principal Liz Phillips said “had little bearing on [children’s] reading ability and yet had huge stakes for students, teachers, principals and schools.” Most of those questions were aimed at assessing the Common Core’s Reading Standards 4-6, which are the ones that look at word choice and structure. Having not seen this year’s tests, I’m not in a position to comment—though if the questions were like the ones I shared from some practice tests earlier, I can see what the concern was about.

Most of the practice test questions associated with those standards were, indeed, picayune and disconnected from the text’s overall meaning. But I don’t think that means that thinking about word choice and structure isn’t important—only that the test questions weren’t very good. Word choice and structure can, in fact, be windows onto a text’s deeper meaning. Or as my colleagues Clare Landrigan and Tammy Mulligan have suggested, thinking about Reading Standards 4-6 can get us to Standards 1-3, which are all about meaning. And so this week, I’d like to apply Reading Anchor Standard 4—”Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choice shape meaning or tone”—to three key buzzwords attached to the Standards—rigor, grit and productive struggle.

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as Stevi Quate and John McDermott, the authors of Clock Watchers, deliberately decided to use the word challenge instead of rigor in their most recent book The Just-Right Challenge. Others, such as former NCTE president Joanne Yatvin prefer the word vigor, which turning to the thesaurus this time, lists synonyms such as energy, strength, gusto and zing. Either or both of those words seem better than one connected to stiff dead bodies—i.e., rigor mortis. Yet rigor is the word that’s most in vogue.

To me, all three seem to have strangely negative connotations. And in that, I’m not alone. Many educators have pointed out that, if we look up the word rigor in the dictionary, we find definitions that suggest something downright punishing. That’s why some educational writers, such as Stevi Quate and John McDermott, the authors of Clock Watchers, deliberately decided to use the word challenge instead of rigor in their most recent book The Just-Right Challenge. Others, such as former NCTE president Joanne Yatvin prefer the word vigor, which turning to the thesaurus this time, lists synonyms such as energy, strength, gusto and zing. Either or both of those words seem better than one connected to stiff dead bodies—i.e., rigor mortis. Yet rigor is the word that’s most in vogue.

The word grit is also popular today and is frequently touted as “the secret to success.” Yet it, too, has a whiff of negativity about it. Grit is what’s needed to get through something

unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as Alfie Kohn notes in his great piece “Ten Concerns about the ‘Let Them Teach Grit’ Fad,” grit seems connected to a slew of other terms, like self-discipline, will power and deferred gratification, all of which push students to “resist temptation, put off doing what they enjoy in order to grind through whatever they’ve been told to do—and keep at it for as long as it takes.”

unpleasant, boring or even painful that someone else has said is good for you—like eating your vegetables or sitting through days and days of standardized testing. And as Alfie Kohn notes in his great piece “Ten Concerns about the ‘Let Them Teach Grit’ Fad,” grit seems connected to a slew of other terms, like self-discipline, will power and deferred gratification, all of which push students to “resist temptation, put off doing what they enjoy in order to grind through whatever they’ve been told to do—and keep at it for as long as it takes.”

Here, too, we could choose another word, like resilience, without the same connotations as grit, but we don’t. According to Merriam-Webster again, resilience focuses on “the ability to recover from or adjust easily to misfortune or change,” not just the stamina or toughness to trudge through it. And as former principal and speaker Peter DeWitt notes in his EdWeek blog post “Should Children Really Be Expected to Have Grit?“, resilience “can coincide with empathy and compassion,” whereas grit seems more about sheer doggedness—and in the case of vegetables and tests, compliance, which may be the word’s hidden agenda.

And then there’s the term productive struggle, which I confess I’ve embraced in the past, as an earlier blog post attests to. I believe completely in giving students time to explore and wrestle with a text in order to arrive at their own meaning because whatever is learned through that process—about that text, texts in general, and the reader himself—will stick much more than if we overly direct or scaffold students to a pre-determined answer. But that word struggle comes with the same negative connotations as the two other words do. The thesaurus, for instance, lists battle and fight as synonyms for struggle, with pains and drudgery as related words. And while I think we can reclaim words—such as turning the word confusion into something to celebrate rather than avoid—I’ve recently started to wonder if we shouldn’t choose a more positive word to get at the same concept, as you’ll see in the twitter exchange I had with two teachers after reading a blog post by the wonderful Annie Paul:

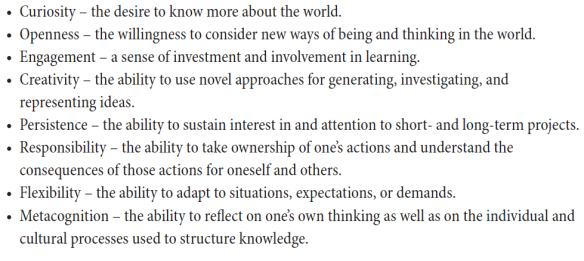

Merriam-Webster defines inquiry as “a systematic search for the truth or facts about something” and unlike the word struggle, which seems mostly connected to hardship and conflict, the word inquiry is connected to questioning, challenge and self-reflection. In fact, it seems to embrace the very habits of mind that NCTE has identified in their Framework for Postsecondary Success:

So what does it say about our culture that the words we’ve chosen to latch on to the most all seem to carry connotations of hardship, toughness and forbearance? Some writers, like Alfie Kohn, see this as simply a new manifestation of the Puritan work ethic—in a time in which it’s become much harder to pull yourself up by your own bootstraps. Others, like P. L. Thomas of Furman University, sees in the “‘grit’ narrative” something much more insidious: “a not-so-thinly masked appeal to racism”, with students of color being tagged as the ones most in need of more rigor, grit and time spent struggling.

In addition to these troubling implications, these three words also focus on student deficits, not on student strengths. And they suggest that we, as teachers, should be like Catwoman with her scowl and her whip, rather than like the Cat Lady who invites children to get to know the kitties. And I can’t help thinking that if, as a society, we chose some of those other words from the NCTE Framework instead—such as curiosity, openness, creativity and engagement—students would engage in productive struggle, even with something deemed rigorous, without explicit lessons on grit. And that’s because . . .

So what would a truly rich task in literacy look like? For me, it seems to be a new way of talking about the kind of problem solving I often ask kids to do, which, in one way or another, involves thinking about what an author might be trying to show us or asking us to consider in a scene, a passage, a line, a whole text. Depending on the text, this might also be framed in a slightly more specific way, as I’ve been doing with one of my favorite finds of the year,

So what would a truly rich task in literacy look like? For me, it seems to be a new way of talking about the kind of problem solving I often ask kids to do, which, in one way or another, involves thinking about what an author might be trying to show us or asking us to consider in a scene, a passage, a line, a whole text. Depending on the text, this might also be framed in a slightly more specific way, as I’ve been doing with one of my favorite finds of the year,