Shortly after the last blog post I wrote, schools around the country began to shut down as the coronavirus upended both our country and our lives. But while the pandemic has been shockingly disruptive, it’s also exposed all sorts of inequities that need to be addressed. Fortunately, though, I’ve found a few silver linings, one of which is collaborating with the wonderful educator and author Maria Nichols on a handful or new projects. What you’ll see below is a repost of a guest post Maria and I were invited to write for the CCIRA blog, followed by some information on a new webinar we’re offering in March.

Like many of you, we began hearing rumors last March that schools might shut down because of a virus sweeping over the country. At that point we couldn’t begin to imagine the full scope of the disruption, devastation and death the pandemic would bring, but we each did begin to find emails in our inboxes postponing or cancelling work we had scheduled—and at some point, in an attempt to make sense of what was happening and to know that we weren’t alone, we reached out to each other and began a journey of thought that continues to this day.

In those first early days, huddled together on Zoom, we talked about supporting teachers and schools as they moved to virtual learning. But we’d scarcely settled on meeting dates and tentative questions to explore when our world erupted again with the murder of George Floyd, which shook us out of our “how do we support literacy as we know it,” focus and led us instead to listen to voices like Bettina Love, who talked about abolitionist teaching, and Sonja Cherry-Paul who challenged us with these words:

All of this convinced us that a return to normal could no longer be our goal. Instead, we wanted to be voices for transformative change, which, in words from David Kirkland’s powerful post “Making Black Lives Matter in Classrooms: The Power of Teachers to Change the World,” recognizes that “Teachers are human rights workers, and our classrooms are progressive vineyards thirsty for liberation’s laborers.”

This wasn’t a difficult shift for us to make, as we’d both been questioning many commonly accepted literacy practices for years. We’d also both been advocating for change, as we believed that the goal of literacy instruction should not just be ensuring students’ mastery of skills, as demonstrated through test scores, but should tap into the deeper, more meaningful aspects of reading and being a reader, which we found was best articulated by writers.

Ursula LeGuin, for example, believed that “We read books to find out who we are. What other people, real or imaginary, do and think and feel is an essential guide to our understanding of what we ourselves are and may become.” And, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley advocated for what he called a “moral imagination,” which we see as a capacity to occupy another mind and feel the emotional pulse of another heart, which reading can support. And that led us to think about whether we had experienced that, ourselves, as children.

I, Vicki, keenly remember reading The Phantom Tollbooth, a book that was given to me by friends of my parents, which I’ve kept all these years. I remember being put off by Milo and his chronic boredom at first. But as I kept reading about his adventures in the strange, confusing world he found himself in, I began to realize that he was changing – that indeed, people could change. They could become kinder, braver, and more helpful, as they started doing things they never thought they could, which I found enormously comforting. And it made me want to become a kinder, braver and more helpful person, as well.

As for me, Maria, the Betsy series by Carolyn Haywood was an early childhood favorite. Oddly, I had all but forgotten that little girl with the brown pigtails until a random day in the school library with my first graders. I was pursuing shelves, hunting for an unexpected literary gem, when a very worn red spine caught my attention: a copy of B is For Betsy! As I thumbed through the musty, fragile pages, memories of Saturday trips to the library with my mom, long afternoons with nothing to do but read, and nights under the covers with books and a flashlight came flooding back. Through this favored series, I had bonded with Betsy, learning to face childhood fears through the comfort of family, true friends, contagious kindness, and the superpower of red ribbons and plaid bookbags. Truly, Betsy helped me construct ways of being as I went out into the world.

As we reflected on these memories, we found ourselves thinking about something else Bettina Love had said: “Why,” she asked, “had it taken a pandemic to see the humanity of all children?” This opened our eyes to the humanity in our own process. We recognized that we had been privileged to have access to texts that helped us see ourselves and create a vision of the people we wanted to be. But we were also aware that we were able to do that without having been taught to “read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it,” or to “determine central ideas of themes of text.” Instead, we did these things by connecting with and being moved by the humanity of a character in a book in a way that helped us become more humane, too. And believing that every child is capable of being moved and thinking deeply, just as we had been, we found ourselves thinking that the transformative change we longed for was a shift from a system based on standardization to one focused on humanization. But what would humanizing the teaching and learning of reading look like?

Before the pandemic, we’d already been asking educators to consider making some key shifts in their practice, which we realized, as we kept talking on Zoom, served the purpose of humanizing classrooms. For instance,

- Shifting from what we saw as a pedagogy of right-answerism to inviting students to think, explore and develop their own ideas.

- Shifting from being a deliverer of content (like comprehension strategies, standards and skills) to becoming a facilitator of student thinking.

- Shifting from seeing confusion as something to be fixed to seeing it as the place where learning and thinking often starts.

- Shifting from seeing learning as something that can be achieved in a single period to seeing it as a much more complex and messy process.

- And, shifting from listening to students in order to assess them to listening in order to better understand their thinking.

These shifts all supported our shared belief that, given the gift of time for students to engage in that messy process, they not only have the ability to intellectually grapple with complexity—they crave it. And to see the effects of these humanizing shifts in action, here’s a conference Vicki had with a seventh grader named Yusef whose class was reading “The Lottery,” Shirley Jackson’s short story about village that, for reasons none of the villagers remember, holds a lottery every year and stones the winner to death.

Yusef had been labeled as a struggling reader, and while many of his classmates jumped into “The Lottery,” Yusef was having a hard time just getting to the third paragraph. When Vicki sat next to him, he pushed the text as far away on his desk as he could, and when she asked if he was wondering anything, he simply said, “This story’s too weird.”

Vicki could have responded in any number of ways, but committed to listening to understand, she leaned into his reaction and asked if he could give her an example of the story’s weirdness, and with that he pulled the story back and accusingly pointed to the second line of the story’s second paragraph:

“The children assembled first, of course. School was recently over for the summer, and the feeling of liberty sat uneasily on most of them; they tended to gather together quietly for a while before they broke into boisterous play, and their talk was still of the classroom and the teacher, of books and reprimands. Bobby Martin had already stuffed his pockets full of stones, and the other boys soon followed his example, selecting the smoothest and roundest stones [to make] a great pile of stones in one corner of the square and guarded it against the raids of the other boys.”

“Right there,” Yusef said. “That’s weird. They just got out of school and it’s like they don’t like it. Man, when I get out of school for the summer, the last thing I want to do is talk about it.”

Here again, listening to understand—and probing student’s thinking without judgment—can reveal surprises. Vicki learned that Yusef’s disengagement with the text wasn’t because it was too hard for him. He just didn’t know how to use his response to engage with the text. And so the first thing she did was validate his response by acknowledging that that was pretty weird. Then she asked if he’d noticed anything else that seemed weird, and he answered, “Yeah, what’s with the stones?”

If you know “The Lottery,” you may be thinking just what Vicki thought: that despite being labeled as struggling, Yusef actually was quite an astute reader who was unaware of that. But noticing and naming could help him begin to see that, so she told Yusef what he’d done: He’d noticed what seems to be a pattern of weirdness, with kids not doing what they usually do, and another pattern around the stones. Then she connected that to the larger work of reading and writing saying: Writers often use patterns to try to show us something they don’t want to come right out and say, and I think it’s possible that the writer actually wants you to pick up all this weirdness and is inviting you to figure out why she put it there. “Hmm. . .,” Yusef muttered, as Vicki gathered her things. But just before she left the classroom, she turned to look back and saw Yusef reading.

As we began sharing stories from our work with students in conferences, small groups and read alouds, we began to brainstorm what we started calling humanizing strategies. Unlike comprehension strategies, these weren’t meant to be explicitly taught to students. Rather they were strategies for helping teachers create more humane and equitable cultures in their classrooms. We broke them into categories, like these examples:

Strategies that can help students take risks with their thinking:

- Unless it’s clearly needed, model who to be vs. what to do, like being someone who’s curious and sometimes confused but who notices things and wonders about them.

- Trust and don’t rush the process of meaning-making—or, as Walt Whitman said, “Be curious, not judgmental.

- Use conditional language, like what might or could something mean vs. does.

Strategies that can help teachers facilitate the often messy process of meaning making through talk:

- Be invitational by asking questions like, “What are you thinking?” or “Is anyone wondering something?”

- Encourage multiple voices by asking questions like “Does anyone have a different idea?”

- Normalize confusion as something every reader experiences and invite students to share what’s confusing them.

- Help students develop a sense of agency by asking how they figured out something that had confused them or that the writer hadn’t explicitly stated.

- Honor students’ tentative thinking, even if you suspect that what they said won’t pan out.

- Help students see that readers revise, just as writers do, by asking if they noticed anything that gave them a new idea or changed their thinking

- Pay attention to students’ expressions and body language, as often there’s thinking behind smirks, grimacing or laughter.

Finally, as we reflect on the whole of this journey, we recognize that all the shifts and strategies we so strongly believe in had the same intention: They were meant to respect and honor students’ intellectual capacities, feelings, and humanity. Perhaps a critical part of transformative change is recognizing that we all want to be seen, heard, and respected – as readers, as thinkers, as human beings.

Finally, if these ideas intrigue you, please join me and Maria at 7pm on March 4 for Part 1 of our two-part Literacy Consultants’ Coalition webinar series “Humanizing the Teaching of Reading: Toward More Meaningful, Authentic and Joyful Practices,” where we’ll share several classroom examples that demonstrate both these humanizing shifts and the brilliance of children and talk about how to implement these in your own classrooms and schools. To register and pay the $25 fee, 10% of which will go to FirstBook, a non-profit organization committed to addressing the systemic causes of education inequity by putting books directly in children’s hands, click here: https://literacyconsultantscoalition.org/humanizing-the-teaching-of-reading/

The British writer and Nobel laureate Bertrand Russell had this to say about about that very question. I love his ideas, but he doesn’t really delve into the instructional role that teachers can play—that is, how can we help students become “readers and thinkers of significant thoughts right from the beginning”?

The British writer and Nobel laureate Bertrand Russell had this to say about about that very question. I love his ideas, but he doesn’t really delve into the instructional role that teachers can play—that is, how can we help students become “readers and thinkers of significant thoughts right from the beginning”?

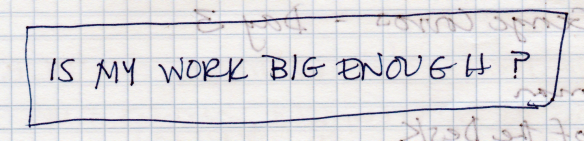

Duckworth

Duckworth

something

something

And in their wise and wonderful book,

And in their wise and wonderful book,

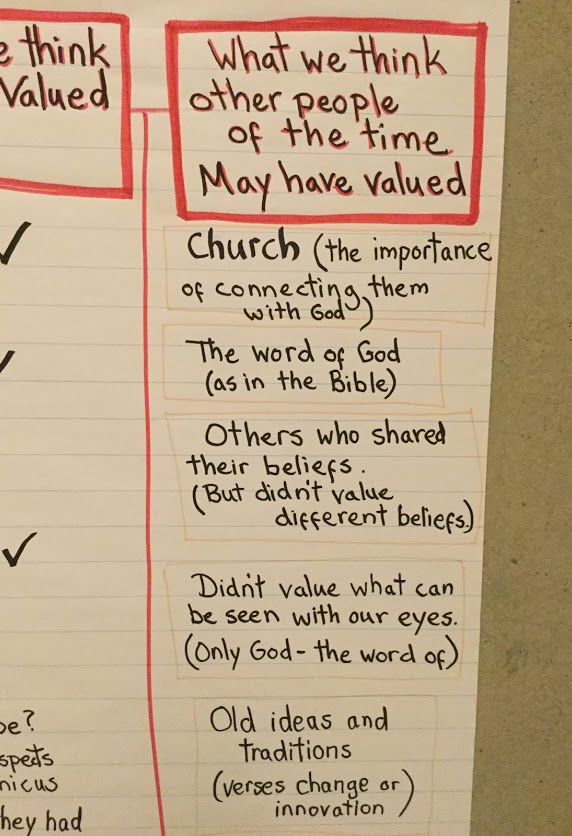

Last year, I had the privilege of working with a wonderful teacher named Keren who taught fourth grade at a small, progressive school in New York City. Every year, students engage in what the school calls a “Big Study”: an inquiry into a topic that was both engaging and broad enough for every child to find a focus of interest. And for several years, the fourth grade’s Big Study was the Middle Ages.

Last year, I had the privilege of working with a wonderful teacher named Keren who taught fourth grade at a small, progressive school in New York City. Every year, students engage in what the school calls a “Big Study”: an inquiry into a topic that was both engaging and broad enough for every child to find a focus of interest. And for several years, the fourth grade’s Big Study was the Middle Ages. And when this happens we need to make some decisions. We can continue full-steam ahead and follow our lesson plans and pacing guides. Or we can keep scaffolding until the students get it (which, if all else fails, means telling them what we want them to get—then feeling relieved when they parrot that back.)

And when this happens we need to make some decisions. We can continue full-steam ahead and follow our lesson plans and pacing guides. Or we can keep scaffolding until the students get it (which, if all else fails, means telling them what we want them to get—then feeling relieved when they parrot that back.)

In each of these cases, I was seeking something that would be good for something I was working on, be it a lesson, a unit, a blog post or a presentation. And the fact that I rarely came up empty-handed makes me believe what the great Persian poet Rumi said—which is exactly what I experienced when the word seek seemed to claim me.

In each of these cases, I was seeking something that would be good for something I was working on, be it a lesson, a unit, a blog post or a presentation. And the fact that I rarely came up empty-handed makes me believe what the great Persian poet Rumi said—which is exactly what I experienced when the word seek seemed to claim me.

same one in those Katharine Hepburn gaucho pants with a cigarette (or palette knife) dangling from her mouth—just as there was something delightful in stumbling on that poem, when it seemed, for a moment, as if Langston Hughes, Walt Whitman and I were connected across time.

same one in those Katharine Hepburn gaucho pants with a cigarette (or palette knife) dangling from her mouth—just as there was something delightful in stumbling on that poem, when it seemed, for a moment, as if Langston Hughes, Walt Whitman and I were connected across time.

The summers of my childhood seemed long and slow and languorous to me, with nothing more important to do than round up some of the neighborhood kids for a game of Kick the Can or find a mom to take us to the pool.

The summers of my childhood seemed long and slow and languorous to me, with nothing more important to do than round up some of the neighborhood kids for a game of Kick the Can or find a mom to take us to the pool. “How do teachers find that balance between offering true, authentic choice, alongside the responsibility for the ‘teaching’ of reading? I don’t know the answer, but I do believe that building a community of readers and writers begins with a teacher who is passionate and who supports a learning environment where empathy is honored, so that risk taking can occur. I always wanted to structure my 7th grade classroom like Atwell’s, where kids can read or write whatever they want, and community is built through poetry. Maybe that’s why her students win so many writing awards… Less structure + More choice = Abundant Learning!”

“How do teachers find that balance between offering true, authentic choice, alongside the responsibility for the ‘teaching’ of reading? I don’t know the answer, but I do believe that building a community of readers and writers begins with a teacher who is passionate and who supports a learning environment where empathy is honored, so that risk taking can occur. I always wanted to structure my 7th grade classroom like Atwell’s, where kids can read or write whatever they want, and community is built through poetry. Maybe that’s why her students win so many writing awards… Less structure + More choice = Abundant Learning!”

“Our reason is not—or at least it should not be—to help students meet the standards we set…[Instead] I believe the most worthwhile goals of writing are: writing to think, to move another person, to create something that will be remembered, to find the most salient personal topics that will weave a common thread through virtually all the writing text in one’s life, to develop a unique personal voice with which one feels at home, to develop and maintain a spirit of unrelenting curiosity that drives the writing forward.”

“Our reason is not—or at least it should not be—to help students meet the standards we set…[Instead] I believe the most worthwhile goals of writing are: writing to think, to move another person, to create something that will be remembered, to find the most salient personal topics that will weave a common thread through virtually all the writing text in one’s life, to develop a unique personal voice with which one feels at home, to develop and maintain a spirit of unrelenting curiosity that drives the writing forward.” Inevitably, what this does is narrow the door for readers in a way that can give them a warped view of reading—and it prevents us from seeing all they might be capable of. To see what I mean, let’s imagine two groups of students both reading the following passage from Patricia Reilly Giff’s

Inevitably, what this does is narrow the door for readers in a way that can give them a warped view of reading—and it prevents us from seeing all they might be capable of. To see what I mean, let’s imagine two groups of students both reading the following passage from Patricia Reilly Giff’s

From my own days in grade school, for instance, there was the English teacher I wrote about in

From my own days in grade school, for instance, there was the English teacher I wrote about in  And then there’s the art teacher who instilled in me a love for visual images, the legacy of which you can see here on the blog. I took after-school art classes from her for years, first in her attic (which had sloping ceilings just like an artist’s atelier in Paris) and then in the incredible studio that extended from the back of her house. Frequently she’d create a still life for us to paint—a bowl or plate filled with apples and grapes, a jug overflowing with poppies—and in spring she’d have us take our easels outside to her garden to paint the flowers, “en plein air,” just as the Impressionists had done.

And then there’s the art teacher who instilled in me a love for visual images, the legacy of which you can see here on the blog. I took after-school art classes from her for years, first in her attic (which had sloping ceilings just like an artist’s atelier in Paris) and then in the incredible studio that extended from the back of her house. Frequently she’d create a still life for us to paint—a bowl or plate filled with apples and grapes, a jug overflowing with poppies—and in spring she’d have us take our easels outside to her garden to paint the flowers, “en plein air,” just as the Impressionists had done.