The title of this week’s post was inspired by Bertrand Russell, who wrote,

When you want to teach children to think, you begin by treating them seriously when they are little, giving them responsibilities, talking to them candidly, . . . and making them readers and thinkers of significant thoughts from the beginning. That’s if you want to teach them to think.

I love Russell’s words for all sorts of reasons, not least of which is the question he seems to raise at the end: Do we really want to teach kids to think—or not?

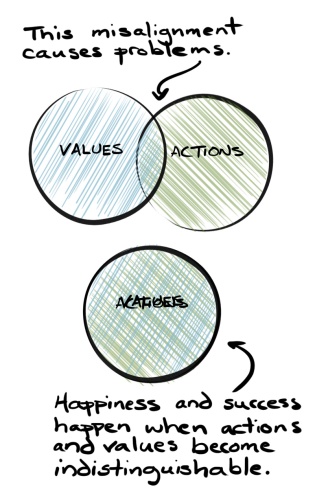

My hunch is that most of us would say we’re committed to teaching children to think. But I sometimes wonder if this is one of those values that isn’t always aligned to our actions—like saying we value growth mindsets, which honor approximations and mistakes, while evaluating students through rubrics that score not how close a student came but whether he ‘got’ something or not.

My hunch is that most of us would say we’re committed to teaching children to think. But I sometimes wonder if this is one of those values that isn’t always aligned to our actions—like saying we value growth mindsets, which honor approximations and mistakes, while evaluating students through rubrics that score not how close a student came but whether he ‘got’ something or not.

As for thinking, I worry that to make sure students ‘get’ whatever we teach them, we often provide too much scaffolding, breaking down complex skills or tasks into bite size pieces or steps that minimize the need for thinking. Or as fourth grade teacher Jeremy Greensmith pithily put it in his interview with Zoe Ryder White for The Teacher You Want to Be,

The danger with a lot of what gets done at the moment is that there’s so much scaffolding that you end up just teaching the scaffold, and you really don’t teach the way of thinking and the way of reading and writing—you just teach [students] to deliver the tool you taught them.”

Of course, Jeremy also raises questions, such as, What do we really mean by thinking? What are the ways of reading and writing? And how do we effectively teach those? And to consider those questions, let’s take a look at a common unit taught in third grade, reading and writing biographies.

When it comes to reading biographies, many units focus on teaching students things like:

- The difference between expository and narrative nonfiction

- The difference between biographies and other kinds of narrative nonfiction

- The structure of biographies (chronological)

- How to identify the traits of a biography’s subject (like you would a character in fiction)

- How to identify the theme, big idea or life lessons of a biography

- How to learn about a historical period through biographies

While some of these objectives require inferring, many involve the kind of thinking found at the first level of Webb’s Depth of Knowledge: identify, recall, recognize, and match. And thinking is even more limited if we offer additional scaffolds, like providing lists of character traits,

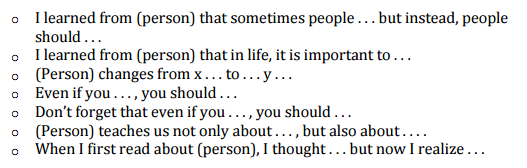

thought prompts,

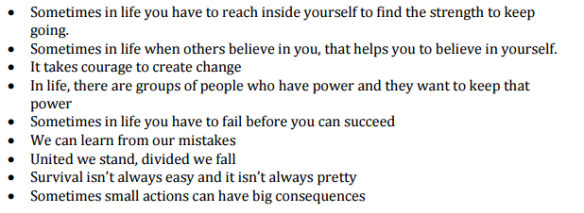

or common biography theme statements.

As for writing biographies, students are usually taught how to take notes, paraphrase, use transitional sequence words, and craft hooks, topic sentences and conclusions, none of which necessarily involves higher order thinking. But what was the deeper thinking work of biographies for readers and writers?

As an occasional biography reader myself (and author of a historical fiction novel), I recognized that a biography is the biographer’s interpretation of the significance of someone’s accomplishments and life, not just an objective recounting. So the thinking work of reading a biography was to try to figure out what the biographer wanted her readers to understand about the subject’s life, while the writing work was figuring out what story do you, as a biographer, want to tell about your subject.

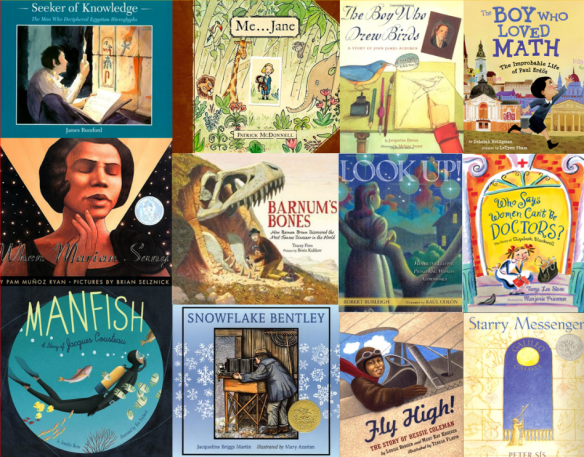

This is exactly the kind of deeper vision of genre I explored earlier, and I kept it in mind as I planned for a day with third grader teachers working on biographies. For the demo lesson I looked for biographies that conveyed slightly different stories about the same subject through the author’s choice of what events to share (and leave out), what words to use to describe those events, and what message she seemed to want readers to take away. And I hit the jackpot with two biographies of George Washington Carver, one from the “Who Was” series of biographies and the other A Weed is a Flower, by the award-winning writer and illustrator Aliki.

In the classroom, I began by asking the kids what they had already learned about biographies, and it turns out they’d met many of the unit’s objectives already through their whole class study of Jane Goodall and their biography book club books. They also said they’d noticed that biographies of the same subject didn’t always contain the same events—which made them think they had to read multiple biographies of the subject they’d be writing about to be sure they knew everything about him or her. And with that I segued to my lesson.

It was possible, I said, that some biographers didn’t have the same events as others because they hadn’t researched enough, but more likely, it was because biographers choose which events and details to include based on what they want us to understand about their subject. And to help us understand that, we’d look at the opening of two different biographies of George Washington Carver and about what each writer might want us to understand about Carver.

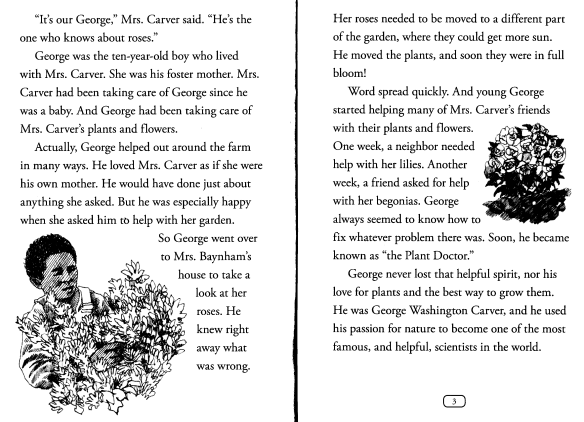

I began with the “Who Was” book, which opens with an anecdote about a woman who “lived in the biggest house in Diamond Grove, Missouri” and was frustrated that her roses weren’t as nice as her friend Susan Carver’s were. So she asked Susan what her secret was and we learn the following:

When the class shared out what they thought the writer wanted them to understand about Carver, they said thinks like, “He was really helpful and hard-working,” “He loved plants,” and “He loved his foster mother.” And with that in mind, we moved on to the opening of A Weed Is a Flower, where the students literally gasped when I read the word slaves.

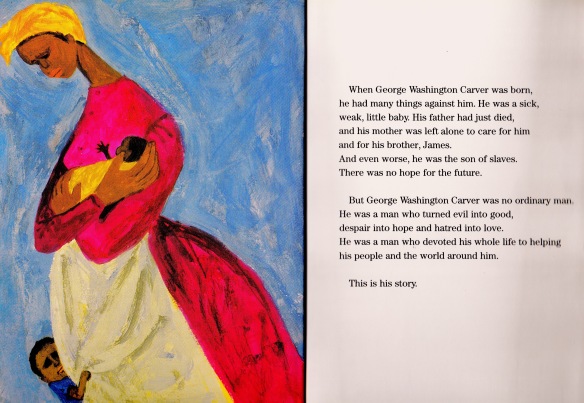

Immediately they realized that Aliki was telling quite a different story about George Washington Carver. Here he was helpful, not simply because he was thoughtful and nice, but because he was committed to helping his people—and his life had been nowhere as pleasant or easy as it seemed in the “Who Was” book. Also they were bursting with questions: Was he still a slave? Did Mrs. Carver own him? What happened to his real mother? and Why did the other author not say he was a slave?

Immediately they realized that Aliki was telling quite a different story about George Washington Carver. Here he was helpful, not simply because he was thoughtful and nice, but because he was committed to helping his people—and his life had been nowhere as pleasant or easy as it seemed in the “Who Was” book. Also they were bursting with questions: Was he still a slave? Did Mrs. Carver own him? What happened to his real mother? and Why did the other author not say he was a slave?

Over the next week they would explore the different choices these authors had made and why, but at that point, I invited them to go back to their tables and think about what story they wanted to tell about their subject by first looking at the books they had read to see what each biographer had emphasized and then to consider what they, as biographers, thought was important. And that required far more thinking than filling in the blanks of a thought prompt or matching a book to a theme statement.

So if we really want to teach children to think, we have to create and give them opportunities to do so—and I’ll share more about that in another post.

This was thought-provoking, Vicki! My question is this: Can complex thinking occur if students don’t have complex language structures such as conjunctions or other words/phrases/frames to describe the relationships between ideas.

Good question, Pam. I think it’s important to begin where they are, but I definitely introduce words like “although” to kids to help them capture the subtlety or nuance they seem to be reading for. And I’d never say never to using sentence templates or prompts, if I felt it was truly needed. I find, though, that kids tend to mirror what we say, so if we keep saying “Now I’m thinking or wondering,” they’ll pick it up quickly. And P.S. It’s been fun being back in touch through the blog & Facebook. Give my best to my old APS friends.

Hello Vicki

Thanks for the thinking. I am now wondering that maybe there is only expository historical nonfiction, as an author wants to me think their way. Is this done mostly by omitting facts and augmenting other facts?

While reading this post I thought more about the concept of significance. In the midst of helping my Year 5 classes with a History inquiry, we are building a timeline together. We are finding that agreeing upon significance of events is not easy. I can’t wait to tell them tomorrow that significance and perspective are connected, and as authors of the timeline, we are making choices that will affect the reader. I think I’m on the right track now, and will enable the students to turn a ‘So what?’ task into something richer. Thanks to you! Exciting times in the Aussie History classroom.

Your comment, Brette, reminds me of a quote of Nietzsche’s that I share in the book: “All things are subject to interpretation. Whichever interpretation prevails at a given time is a function of power and not truth.” The trick is to make sure that the interpretation is, in Louise Rosenbatt’s words, coherent. That is, that it doesn’t ignore details, facts or events that don’t fit. But definitely empower them to interpret. It’s actually what historians do!

… “significance and perspective are connected” – I guess I knew that, but stating it so clearly has given me pause for thought… it’s a “big idea” for kids and adults.

Vicki,

I love this post. I teach gifted kids. They often see things differently and need to be challenged beyond the simple scaffolds, but these scaffolds are making them into lazy thinkers. I have been struggling with how to create opportunities that ask them to think more deeply. This past year, I used Carole Boston Weatherford’s book about Fannie Lou Hamer as well as a YouTube video of her testimony. Then they had to compose an essay with their own claim about Fannie Lou Hamer’s life. If you ask my students, they would say this was the lesson they hated the most, but to me, it was the best because I made them think. Thinking is hard work. Thanks for valuing this and helping us in the trenches understand how to move beyond the scaffolds.

I’ve worked with gifted kids, too, Margaret, and they can be challenging because they don’t always like to get out of their comfort zone and risk not being right. Sounds like this may have been the case here, too. My experience was that engagement was key – and sometimes it was as hard for them to get really engaged as it is getting kids who are disaffected because they can be so risk averse. Lots of low risk tasks often helped that. But I definitely get that it can hard.

Vicki,

I’m thinking about how two texts for deeper genre study by teachers could also stimulate deeper conversations and thinking. Prompts, stems, questions and lists all begin with good intentions and YET in the absence of unlimited time or “time as the enemy”, choosing a trait from the list becomes “easier” than the thinking. So again, slowing down, doing less, going deeper wins out and I do believe that “carry over” to following years and units can be very helpful to build connections and help TEACH for TRANSFER!

❤

Yes to slowing down! Yes to doing less! And yes to going deeper! I think many teachers also see the easier route as more efficient because it gets the job done quickly. But if kids aren’t able to retain, transfer and apply what was taught, the teaching simply wasn’t effective. Also learning to learn takes time; there’s simply no way around it. But my hunch is that both you and I think it’s the single most important thing to learn.

Vicki, you are doing amazing work. Your last few posts have really hit THE educational nail directly on the head. In a Pinterest, Teachers Pay Teachers world, we need to rise up against “cute” activities that devalue deep thinking. Thank you for your eloquent thoughts and keen wisdom.

Thanks so much, Lisa! I really appreciate the vote of support!

Pingback: OTR Links 05/31/2017 – doug — off the record

Thanks for spreading the word, Doug.

What a magnificent post! And the books. You give student so much to think about but served in a way that is accessible (no small feat!. With the realization that nonfiction writers make choices in what they tell us gives a motivation to think. We can’t just accept one writer’s words. We as readers are obligated to read knowing the interpretation of “fact” can be skewed. That Nietzsche quote just nails it!

Pingback: Thinking about Thinking: The Power of Noticing | To Make a Prairie

Pingback: A New Year with an Old Friend: Some Thoughts on My One Little Word | To Make a Prairie

Pingback: Creating Opportunities for Students to Think | To Make a Prairie