A few weeks ago I invited teachers to construct an understanding of the deeper purposes of realistic fiction and then shared their ideas in a follow-up post. And last week I shared a lesson that helped fourth graders construct a deeper understanding of how scenes and details work. In both cases I, in the role of teacher, created opportunities for learners to invent new knowledge, and pedagogically that’s quite different than the kind of direct instruction with modeling associated with writing workshop mini-lessons.

As a teaching practice, creating learning opportunities goes by many names. In his great book Mentor Author, Mentor Texts, Ralph Fletcher borrows a term from the world of computer programming and calls it an “open source” approach to teaching craft. Instead of teaching a specific craft move through a mentor text—which, as Ralph notes, “runs the risk of reducing a complex and layered text to one craft element”—an open source approach invites students to “look at these texts and enter them on their own terms,” which “gives students more control, more ownership.” While Katie Wood Ray describes this practice in her wonderful book Study Driven as an “inquiry approach” to teaching and learning, where students are similarly invited to notice and discover what writers do then try on the moves they’d like to emulate.

Whatever we call the practice, however, it’s directly connected to the constructive theory of teaching and learning espoused by educators like Dewey, Piaget, Vygotsky and Bruner. With some slight differences, each of these great minds thought that students retain, understand and are more likely to apply and transfer what they’ve actively constructed than what they’ve been more explicitly taught. And these ideas hold many implications for what it means to teach, such as the following:

While there are times I do teach through direct instruction and modeling, I increasingly use constructivist practices with both students and teachers. For students, for instance, who need additional time to wrestle with the concept of scenes versus summaries, I like to share the following two pieces by Lois Lowry about the same event and invite them to consider how they’re different in order to construct a deeper understanding of the purpose and craft of scenes.

The first is from her memoir Looking Back:

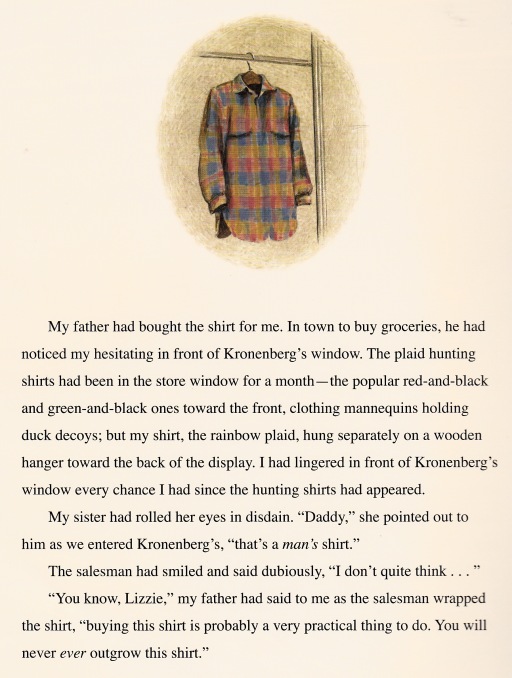

I was nine years old. It was a man’s woolen hunting shirt. I had seen it in a store window, it’s rainbow colors so appealing that I went again and again to stand looking through the large window pane. The war had recently ended, and my father, home on leave before he had to return to occupied Japan, probably saw the purchase as a way of endearing himself to a daughter who was a virtual stranger to him. If so, it worked. I remember still the overwhelming surge of love I felt for my father when he took me by the hand, entered Kronenburg’s Men’s Story, and watched smiling while I tried the shirt on.

I was nine years old. It was a man’s woolen hunting shirt. I had seen it in a store window, it’s rainbow colors so appealing that I went again and again to stand looking through the large window pane. The war had recently ended, and my father, home on leave before he had to return to occupied Japan, probably saw the purchase as a way of endearing himself to a daughter who was a virtual stranger to him. If so, it worked. I remember still the overwhelming surge of love I felt for my father when he took me by the hand, entered Kronenburg’s Men’s Story, and watched smiling while I tried the shirt on.

And this is from her autobiographically inspired picture book Crow Call:

Practices like these—which ask students to explore the question, What is a scene and how do writers write them?—are also related to the problem-based approach to teaching math that’s increasingly being embraced, as well as to what I advocate for in my new book on reading. But for reasons I don’t completely understand, these practices haven’t taken much hold in literacy. Perhaps, it’s because they can take more time than a typical mini-lesson does or because, being open-ended, they can be messier than direct instruction. If you believe, though, that the ultimate goal of teaching is the transfer of learning, as the late, great Grant Wiggins does in one of his final blog posts, then we have to consider the findings of a research study that compared the affects of direct instruction (DI) and what they called discovery learning through problem solving practice (PR) over time:

As you can see from the chart, students engaged solely in discovery learning—who constructed their own understandings of content through grappling and practice—demonstrated consistent growth in learning over time. The combination of students receiving both direct instruction and discovery learning ultimately reached the same level of learning, despite a somewhat precipitous drop along the way. But those who only received direct instruction were able to transfer less.

For the record, this study involved fourth graders presented with a science problem, not a literacy one. But as I wrote in an earlier post, I think the process of constructing an understanding by developing hypotheses about what you notice that you then test out, refine and revise into theories, can be the same across the disciplines. It’s also worth noting that, whether we call this an open source, inquiry, constructivist or problem-based approach, there’s still lots of teaching to do.

As you can see with my Ruby the Copycat example, I nudged students to deeper thinking by raising probing questions and inviting them to be more specific and precise about what they’d noticed. And from that, I named what they’d noticed in more generalized language so students could apply and transfer it to their own work. And you can see the masterful Kate Roberts do the exact same thing in a video of her working with middle school students studying a mentor argument text.

You could say that both Kate and I set students up to notice things we might ordinarily teach through direct instruction, which, as Katie Wood Ray says in Study Driven, allowed them to uncover content versus receive it, which can deepen understanding. And finally there’s another reason to add this powerful practice to your teaching repertoire. According to Jerome Bruner, “Being able to ‘go beyond the information’ given to ‘figure things out’ is one of the few untarnishable joys of life.” So if you want to bring more joy to your classroom, consider creating opportunities for students to construct their own understanding, versus always teaching them directly.

You could say that both Kate and I set students up to notice things we might ordinarily teach through direct instruction, which, as Katie Wood Ray says in Study Driven, allowed them to uncover content versus receive it, which can deepen understanding. And finally there’s another reason to add this powerful practice to your teaching repertoire. According to Jerome Bruner, “Being able to ‘go beyond the information’ given to ‘figure things out’ is one of the few untarnishable joys of life.” So if you want to bring more joy to your classroom, consider creating opportunities for students to construct their own understanding, versus always teaching them directly.

I left teaching art in 1986 because I thought the inquiry/problem solving approach in the art room made sense for every subject. After attending a grad school seeped in constructivist approach (Sarah Lawrence’s Art of Teaching program) I am still swimming upstream.

It seems even harder with all the more mandated curriculum and a standards driven approach to teaching. Getting kids to think and reason should be the goal. Those “skills” can be universally applied. But when we follow writing recipes, predetermined lists,

little choice, and so on — we offer little opportunities for kids to think or reason.

Funny thing is the buzz word is inquiry in Social Studies. Maker Spaces now abound and problem solving in new engineering programs is “so 2016”! but

Yet open ended/thinking/inquiry is still pooh poohed in reading and writing…no one trusts kids enough. When instruction is in a neat little box the learning is often rote and teachers complain & winter why there’s “no transfer”. It all feels very Kafkaesque to me but after 24 years in the regular classroom I have not given up yet… but my arms are getting tired from going against the current.

Thanks again for putting a spotlight on important ideas!

Hello Claudia! It is strange, isn’t it, that other disciplines have embraced inquiry/problem solving approaches but literacy hasn’t. I’ll be making an even bigger case for it in the new book, where, as you said, I make thinking the ultimate goal–and where I try to show that you can meet the CCS that way, as a by-product of authentic deeper reading and thinking. But if you have the time for a professional read, you might want to check out Cultures of Thinking by Ron Ritchhart from Harvard’s Project Zero. He, too, makes a really strong case and has more research to prove it.

Thanks! I will definitely look for Cultures of Thinking. (I am currently reading Making Thinking Visible – thanks to reading so many of your posts.)

Thanks so much for your thinking post. Our students are over taught and under practiced for sure!

Students are not empty vessels to be filled up but too much of the school day is STILL filled with teacher talk and what seems like student imitation . . . sometimes! Without a doubt, the label is the least important but I’m sure it causes the most confusion as some teachers have to be able to put this work into a neat little pigeonhole and yet will agree “whether we call this an open source, inquiry, constructivist or problem-based approach, there’s still lots of teaching to do.”

Just wondering here:

Is it fear of teaching differently from a teammate across the hall?

Is it fear that students won’t get it because the teacher (himself/herself) is struggling with the “constructivist” approach?

Is it lack of deep understanding by teachers because they weren’t taught this way?

Do the multiple standards make it seem like “Mission Impossible” as there would be NO WAY to teach all this way so time rules it out?

I’m remembering a fabulous constructivist teacher who was marginalized by her peers for being different but those students learned and learned and learned as I did. Inquiry is “back” in science and social studies but I wonder if it’s true student inquiry or if it’s more of a dot to dot “choose a topic” work!

Hi Fran! Those are all great questions, and may be true to varying degrees. I would also add: is it strong pressure to use certain programs even when they go against our informed opinions about best practices? Is it because we (admin included) don’t match our beliefs with our practices? Is it because we say we do what’s best for kids, but we focus more on achievement (which I argue is more about the grownups in the equation) rather than learning (which is about the kids)? Is it fear of being evaluated lower if you don’t conform to these pressures, and fear of losing your job? I know that sounds extreme, but I have to say, that’s where I’m at right now. If I was simply rated lower and that was the end of it, I could live with that. But my performance rating is tied to keeping my job, and that’s an awful position to be in.

Great questions and I would even modify your first one to say: “Are you required to use a program?” and then if the response is “yes”, “Are you allowed to modify that program?”

Fran, Yes to the first question, and no to the second one. 😦

It is, indeed, incredibly awful that teacher evaluations are sometimes being based on ‘fidelity’ to a program, not ‘fidelity’ to kids and deeper learning. The other big question is how do we help administrators understand the limits of packaged programs?

Over taught & under practiced! You nailed it! And I think that’s because we focus too much on coverage and achievement versus deeper learning. I also agree with all your wonderings; they all seem to come into play, as does too much PD that’s focused on training not deeper understanding. But it’s my dearest hope that the tide is changing, at least in some places. And I’ll be sharing more research that suggests that, as research does seem to make people stand up and take notice more.

Thank you again, Vicki, for another well-timed post. More and more I’m realizing that so often what we do doesn’t match up with what we believe, or at least, what we SAY we believe. I think your response to Julieanne’s comment in last week’s post really nailed it: we are focused more on “achievement” (which is really more about teachers and admin) than LEARNING (which is all about the students). And I do think that one reason we don’t do more constructivist-type teaching is that it takes longer. But, the payoff is worth it in the end: if we let kids construct their own understanding with guidance from us. ultimately students’ learning is deeper, plus we don’t have to go back and reteach- which adds it’s own extra time.

Really looking forward to your new book, and wish I could chat with you more often. Grateful you are blogging more often now which enables a virtual chat with you. 🙂

You’re right, Alison, that there’s a real disconnect with what we say we value and belief and what we actually do. And I get that time is an issue. BUT . . . if we really do believe that the ultimate is deep learning with the ability to apply and transfer, as Grant Wiggins does, the time is justified. Who, after all, really learns anything substantial without lots of exposure and practice? Not me, who’s taken Beginning Italian four times! And you’re absolutely right, as well, that without that commitment of time we wind up reteaching anyway and spending too much time on test prep, none of which is terribly engaging for students. But . . . I’ll be taking to the blog again when I get back from Qatar with more on this because it feels REALLY, REALLY important!

I’ve commented on this fantastic blog post Vicki, on FB and other places. Here, in the company of the brilliant Fran and Allison, I will admit that when I am demonstrating writing work in schools, I often feel so guilty, even under-prepared, when I simply ask kids what they notice about a text. You’ve not only assured us this is a good thing for learning, but you even back it up with links to research! Thank you for this. I feel more confident heading into this week’s PD.

Oh, my goodness, Katherine. What a compliment- thank you.

Isn’t Vicki brilliant?

Seems important to highlight here that even Katherine Bomer can be anxious and worry, just as I can, too, when we open the door wider–because we don’t know what the kids will say and that can be scary. It’s a leap of faith that does require some trust. Trust in the process of learning, trust in the kids and trust in ourselves, which may be the hardest of all. But with all the talk of mindsets in the air, it’s important to remember as well that if we want kids to take risk and try new things, we have to be willing to do that, too!

Oh, Katherine, so nice to see you here! I think the thing to remember is that if kids don’t notice much the first time we ask, we can always jump in and do a little modeling. But we don’t know what they can do if we never open the door wide often for them to show us. We should also remember that they’ll get better with practice and exposure. I remember a HS I worked in in the city and the first time we asked the kids what they noticed an author doing they had virtually nothing to say. And by the end of the year, it was amazing how much they noticed–and how much they tried to replicate in their own writing. Also think that showing kids two examples of something can make this easier, as difference can stand out. Then their job is to figure out how to articulate what they’ve noticed, and we can help them out with that–just like I know you do & write about so brilliantly in Hidden Gems!

Pingback: What’s in a Word: Some Thoughts on Learning & Achievement | To Make a Prairie

Pingback: Counting Down to Dynamic Teaching for Deeper Reading: What Does It Mean to Teach Dynamically? | To Make a Prairie