© D. A. Wagner 2012, dawagner.com

Over the last few weeks I’ve found myself reflecting a lot on how much has changed in the educational landscape and my own thinking since What Readers Really Do came out two and a half years ago. And having also spent some time last month working with Lucy West, Toni Cameron and the amazing team of math coaches that form the Metamorphosis Teaching Learning Communities, I want to share some new thoughts I’ve been having about the whole idea of scaffolding.

From what I could gather from a quick look at (yes, I admit it) Wikipedia, the idea of scaffolding goes back to the late 1950’s when the cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner used it to describe young children’s language acquisition. And by the 1970’s Bruner’s idea of scaffolding became connected with Vygotsky’s concept of a child’s zone of proximal development and the idea that “what the child is able to do in collaboration today he will be able to do independently tomorrow.”

Even before the Common Core Standards, teachers have been encouraged to scaffold by using scaffolding moves like those listed below (which were culled from several websites):

- Activating students’ prior knowledge

- Introducing a text through a short summary or synopsis

- Previewing a text through a picture walk

- Teaching key vocabulary terms before reading

- Creating a context for a text by filling in the gaps in students’ background knowledge

- Offering a motivational context (such as visuals) to pique students interest or curiosity in the subject at hand

- Breaking a complex task into easier, more “doable” steps to facilitate students achievement

- Modeling the thought process of students through a think aloud

- Offering hints or partial solutions to problems

- Asking questions while reading to encourage deeper investigation of concepts

- Modeling an activity for the students before they’re asked to complete the same or similar one

© D. A. Wagner 2012, dawagner.com

As I looked at in last year’s post on Common Core-aligned packaged programs, scaffolding these days has been ratcheted up even more, with teachers more or less being asked to do almost anything (including doing a think-aloud that virtually hands over the desired answer) to, in the words of one program, “guide students to recognize” and “be sure students understand” something specific in the text. And, for me, that raises the question: What is all that scaffolding really helping to erect or construct? Is it a strong, flexible and confident reader who’s able to independently understand all sorts of texts? Or is it a particular understanding of a particular text as demonstrated by some kind of written performance-based task product?

If we think about what’s left standing when the scaffolding is removed, it seems like we’re erecting the latter, not the former—though in What Readers Really Do, Dorothy Barnhouse and I attempted to change that by making a distinction between what we saw as a prompt and a scaffold, which can be seen in this chart from the book:

Most of the scaffolding moves listed above don’t, however, follow this distinction. Many solve the problems for the students and are also intended to lead students to the same conclusion— a.k.a. answer—as the teacher or the program has determined is right. I’m all for reclaiming or rehabilitating words, but given that the Common Core’s Six Shifts in Literacy clearly states that teachers should “provide appropriate and necessary scaffolding” (italics mine) so that students reading below grade level can close read complex texts, redefining the word scaffold may be a bit like Sisyphus trying to push that boulder uphill. So I’ve been thinking (and here’s where the math folks come in) about recasting the kinds of scaffolds Dorothy and I shared in our book as what my math colleagues call models.

a.k.a. answer—as the teacher or the program has determined is right. I’m all for reclaiming or rehabilitating words, but given that the Common Core’s Six Shifts in Literacy clearly states that teachers should “provide appropriate and necessary scaffolding” (italics mine) so that students reading below grade level can close read complex texts, redefining the word scaffold may be a bit like Sisyphus trying to push that boulder uphill. So I’ve been thinking (and here’s where the math folks come in) about recasting the kinds of scaffolds Dorothy and I shared in our book as what my math colleagues call models.

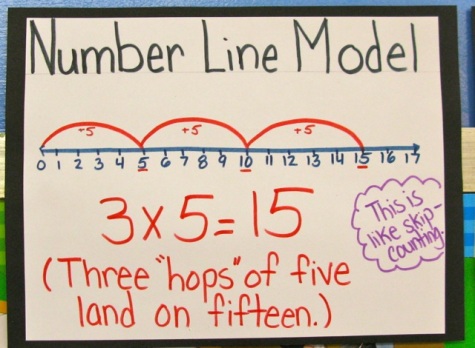

Models in math are used not only as a way of solving a problem but of understanding the concepts beneath the math (which Grant Wiggins has just explored in a great “Granted, and. . . ” blog post). Here, for instance, are two models for multiplication: The first is a number line which shows how multiplication can be thought of as particular quantity of another quantity (in this case, three groups of five each), and the second the Box Method, or an open array, shows how large numbers can broken down into more familiar and manageable components and their products then added up. Each model is being used here to solve a particular problem, but each can be immediately transferred and applied to similar problems:

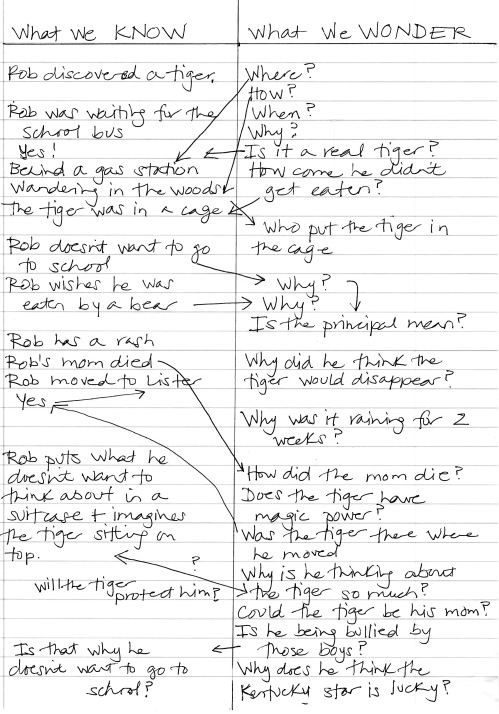

And here’s a text-based Know/Wonder chart that records the thinking of a class of 5th graders as they read the first chapter of Kate DiCamillo’s wonderful The Tiger Rising (and—sneak peak—will be appearing in my next book):

© Vicki Vinton 2013, adapted from What Readers Really Do by Vicki Vinton and Dorothy Barnhouse (Heinemann, 2012)

Like the math models, it references the specifics of a particular text, but it’s also a model for solving certain kinds of problems—in this case, how readers figure out what’s going on at the beginning of a complex texts and develop questions they can use as lines of inquiry as they keep reading. In effect, the chart makes visible what those students were “able to do in collaboration” that day that they’ll “be able to do independently tomorrow,” because, whether we call it a scaffold or a model, it’s directly and immediately transferrable to other texts that pose the same problem.

In the end I don’t think it really matters what we call this kind of support, but I do think we have to ask ourselves what, exactly, we’re scaffolding or modeling. Are we helping students get a particular answer to a particular problem or text in order to produce a particular assignment? Or are we, instead, really offering a replicable process of thinking that’s tied to the concepts of a discipline, which can start being transferred tomorrow not an at indeterminate point in the future? Of course, that raises the question of what the underlying concepts in reading are, which we don’t talk about as much as my math colleagues do for math. But that I’ll need to save for another day . . . .

Vicki,

This is so critical! Are we “teaching the reader or the text?” Are we “teaching the writer or this piece?” are questions that constantly discussed at TCRWP. So is the goal “independence” and even “transfer” across curricular areas? If yes (my hope), then we must make sure that students have many opportunities to interact without the scaffolds and even prompts as they near that “independent” signpost!

I’m also thinking about this series of questions – “What is all that scaffolding really helping to erect or construct? Is it a strong, flexible and confident reader who’s able to independently understand all sorts of texts? Or is it a particular understanding of a particular text as demonstrated by some kind of written performance-based task product?” How do we move to belief and understanding about the so valuable LEARNING for our students???

Great thinking along with you!!!

Thanks, Fran. I’m reminded of a conversation I had with a principal many years ago. He and his teachers decided to start the year with students reading a book below their F&P level to see how much inferring they could do. And guess what? Most of the kids were able to infer automatically with a text they could easily access. We’re over scaffolding in order to get kids to ‘get’ complex texts way above their level, and too often nothing is sticking—except for a dislike of reading. As Tom Newkirk says in his great post on Speaking Back to the Common Core, perhaps “a much more plausible road map for creating readers who can handle difficulty” is to slow down the process and build on their strengths in texts that are more in their reach and with scaffolds they can apply more immediately.

Tom Newkirk’s idea makes so much sense. Unfortunately we won’t do that as the “harder is better” regime seems to be in power.

Great for me to remember as I work with teachers though as our key words this year are “independent” and “transfer”!

Funny thing – that first chart was much on my mind when I re-read your book this summer. That, and the book, made me rethink reading workshop and the type of scaffolding I practice. Such a thoughtful post, Vicki – you always push my thinking!

So interesting, Tara. I think many of us are on parallel journeys as we see the damage some of the narrow interpretations of the Common Core has caused—in this case using scaffolds that actually disenfranchise and disempower students. So glad this touched a chord!

Two things that really popped out for me that feel so important about scaffolds are that they are transferrable and that they are flexible. If a tool cannot be used in multiple situations and for multiple purposes, and if it is not designed to be removed, it is not a scaffold. Also, of course teachers must instruct students on how to use scaffolds, but then the scaffolds should gradually be left in students’ hands, to choose when and how (and how long) to use them. Thanks for another wonderful and timely post.

Thanks, Anna. In addition to your great rules of thumb for using and teaching with scaffolds, I’d like to add that we not only need to instruct students how to use them but we need to make sure they’ve actually experienced the power those scaffolds can offer them as readers. Without that I’m not sure how they develop the motivation to use them themselves as it becomes another thing we tell them to do, not that they necessarily see AND feel the value of.

This is such an important post! Thank you for thinking through and for presenting the info so clearly. I too have wrestled with how much to scaffold for students, and for adult learners and for how long. It seems the sooner we can remove the scaffold, the better. Sending learners off to inquire and grow their theories and ideas on their own, and to find their own answers is certainly always the goal – independence! Last week in study at Teachers College, I noticed how very much they “tucked” into each day. Seems that teaching students and adults as well to ask the big questions is also important, letting us grapple with new concepts and ideas grows us as learners. Less scaffolding supports this type of inquiry.

I will keep these questions at the fore as I work with learners:

“Are we helping students get a particular answer to a particular problem or text in order to produce a particular assignment? Or are we, instead, really offering a replicable process of thinking that’s tied to the concepts of a discipline, which can start being transferred tomorrow not an at indeterminate point in the future?

Replicable and transferrable – now that’s a strategy!

Thank you for sharing your good work.

So agree with you that “the sooner we can remove the scaffold, the better.” That may mean students are approximating more but I think that’s a necessary step to learning anything deeply. And in ways I’m not sure I can fully articulate yet, those approximations complete with missed steps seems connected to those great questions you raised in your post about valuing with accuracy, which was great.

Such a centering post. And so important to keep in mind as we start the year.

It is easy to be sidetracked by the call to “meet” the standard which could feel like guiding a lamb to slaughter not nurturing a learner on their path to success. As I enter a new year the image of a scaffold that seems to cage will stick.

Yes to no more guiding lambs to slaughter & no more scaffolds that cage instead of free! Words to hold on to as I head to LA.

Love this post, Vicki. It is fun to see how you are connecting fields of study/thought (math and reading) so fruitfully. I’ve been reading Tom Newkirk’s MINDS MADE FOR STORIES (intellectually exciting, as well as a good read!) and some stuff about science ed. and couldn’t help but make some connections with what you’ve said here. Maybe one of the things a good model does is to help learners compose a narrative about what they are learning, to help us recognize patterns, to help us create some provisional meaning to our new experience, to give us (as scientists do) a starting place for a conversation with others. Newkirk (quoting Peter Elbow) notes that narrative is a way to “bind time.” I suspect that one thing good models do is help us create narratives; created in the moment of learning, they become artifacts we can unpack and interpret to see where we’ve been and, perhaps, where we might go?

It’s been a good summer for thinking for me—and can’t wait to get my hands on Tom’s new book. And what you’re suggesting about models, narratives & artifacts feels like the kind of documentation they talk about in Reggio Emilia, which I’ve been revisiting in my head for an essay I’m working on about that experience. I just love when all this stuff connects—and I haven’t even started A More Beautiful Question!

Very insightful post…loving the distinction between the scaffolding and prompting. If we are truly creating independent thinkers, then we need to be sure that we are guiding them to come to their own conclusions.

Love your “if, then” sentence! I wonder how else we might finish the sentence by using your beginning: “If we are truly creating independent thinkers, then . . . ” And how much of what comes after the ‘then’ isn’t the focus of so much of what passes for Common Core instruction. You got me thinking! Thanks

Excellent post! I found the prompt vs. scaffold chart and the What We Know/Learn model very useful. Thanks for the affirmation,

So glad this was useful, Brad. It definitely seemed to hit a chord as people start a new school year—even more so than when the book first came out. Perhaps having been ask to do anything it takes to help students ‘get’ texts they can barely access, the time is now ripe for all of us to question such overly scaffolded experiences.

Pingback: The Third Annual Celebration of Teacher Thinking | To Make a Prairie

Pingback: Mind the Gap: What Are Colleges Really Looking for in Student Writing | To Make a Prairie

Pingback: Counting Down to Dynamic Teaching for Deeper Reading: Delving into Deeper Reading | To Make a Prairie

Pingback: Interpreting Interpretation: A Look at an Overlooked Word | To Make a Prairie

Pingback: Creating Opportunities for Students to Think | To Make a Prairie