I began thinking about this post last Thursday after I’d spent the day with some teachers who were trying to wrap their minds around what makes a nonfiction text complex beyond background knowledge and vocabulary. I’d brought a sampling of books with me, many from the list of text exemplars found in Appendix B of the Standards, and as the teachers began to pour through them, they noticed many things. They noticed, for instance, that most of these books disrupted much of what we teach students about nonfiction; many had illustrations, for instance, instead of photographs, and many had no text features to speak of—no table of contents, no index, no subheadings, to make fact retrieval easy. And rather than the dry, utilitarian language we often find in nonfiction, these books were filled with the kind of language more often associated with poetry, as can be seen from this gorgeous page from Nicola Davies‘s book Big Blue Whale:

“I wish I could find a teacher who’d do an author study of Nicola Davies with me,” I said as I imagined children writing ‘information’ texts that explored content through beautiful language that made facts come alive and were structured as creatively as these text exemplars were, rather than by drearily following the Writing Standards bullet points like a formula.

That, in turn, gave birth to several wishes that Thursday afternoon. I wished that in this current climate of argument, analysis and evidence, we could find the time not just to “determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative and connotative meanings,” but to relish and delight in language and feel its power to move us. And to do this, I wished, as Tom Newkirk does in his wonderful piece “Reading Is Not a Race: The Virtues of the ‘Slow Reading Movement‘”, that we could stop equating proficient reading with speed and right answers and instead, “not put students on the clock, but to say in every way possible—’This is not a race. Take your time. Pay attention. Touch the words and tell me how they touch you.'”

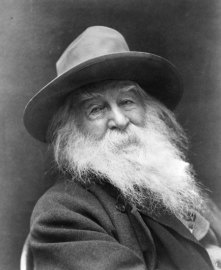

I also found myself wishing that we could crack open those first three writing Standards and acknowledge how truly powerful writing doesn’t always fit comfortably and neatly into those opinion, information, and narrative categories—even when we’re writing about texts. Here, for instance, is a link and an excerpt to writer, professor and educator Tom Romano‘s glorious essay “A Relationship with Literature,” which combines personal narrative, literary analysis and deeply held convictions to explore his life-long relationship with Walt Whitman:

I also found myself wishing that we could crack open those first three writing Standards and acknowledge how truly powerful writing doesn’t always fit comfortably and neatly into those opinion, information, and narrative categories—even when we’re writing about texts. Here, for instance, is a link and an excerpt to writer, professor and educator Tom Romano‘s glorious essay “A Relationship with Literature,” which combines personal narrative, literary analysis and deeply held convictions to explore his life-long relationship with Walt Whitman:

“Through their essays students have shown me that literature matters to them for many reasons: because of their search for identity, their spiritual needs, their desire to escape to imaginative worlds, their evolving sense of justice. . . . No students yet have written that what won them over to literature was the arc of the Victorian novel, or the qualities of Romanticism, or what a green light symbolized at the end of a dock. This doesn’t surprise me. Literature matters to my students because of their wild and precious lives. They want them to make sense, to be meaningful. They want to find their way. And I understand. ‘I am the man. I suffered. I was there.’ (Whitman).”

And then, of course, came last Friday, when yet another unimaginable act of violence occurred, destroying 27 wild and precious lives. Tom Romano notes that some of his students “have come through slaughter, and a book helped them understand that pain, fear and despair.” I do wish that at some point the families of Newtown, Connecticut, will find some shred of solace in a writer’s words. But right now I wish that literature will fail us, that it actually won’t help us make sense of what happened, because if understanding begets acceptance and tolerance, I wish to never understand what happened that day and to never, ever have to see the words massacre and school in the same sentence again.

Finally, as we head into the holidays, I wish that we might find the strength and courage to to change a world that seems bent on discounting creativity, beauty and the slow accretion of meaning, that seems to care more for the rights of gun owners than the rights of children, and that narrowly evaluates the value of a teacher in ways that fail to acknowledge the valor and sacrifice of the teachers in Newtown. Of course, doing that will not be easy. But for that we might want to hold on to the words of Anais Nin‘s poem “Risk”:

And then the day came,

when the risk

to remain tight

in a bud

was more painful

than the risk

it took

to blossom.

Beautiful.

Happy holidays, Maggie! And by the way, I loved your Reggio reflection!

Vicki, this is written with such a beautiful sensitivity. Thank you!

Renee

Thanks for sharing these beautiful thoughts and Anais Nin’s perfect poem.

The poem was another gift from NCTE. Sir Ken Robinson shared it in his keynote address and it seemed too good not to pass on.

Thank you for once again reminding us of the power of touching the words and letting them touch us. Your words have inspired and touched us once again.

So nice to hear from you Dwaine! For some reason I still get the occasional email from the Hotel Derek, and each time I think about you, Micky and the crew at Lanier. So please pass my holiday wishes on. And here’s hoping that our paths get to cross again at some point in the future.

Thank you for smoothing the ragged and raw into the language I speak and reminding me that cherishing and sharing words can bring sweetness into the searing void of sorrow.

Thank you for the beautiful and inspiring post. Merry Christmas.

I have to say, Ellen, that I was keenly aware that this was not the first time this year that I felt compelled to write about something that encompassed both guns and teachers. But maybe, maybe, we’re moving toward a change. In the meantime, hope you enjoy the holidays, too. And hope that our paths cross again soon!

Thank you for saying what needs to be said so beautifully.

Thank you.

Amen!

Absolutely beautiful and touching words to live by. May your wishes come true.

Have a wonderful Holiday and I look forward to more of your amazing ideas in the new year.

Same to you, Maribeth. May our jointly held wishes come true!

I have never been a fan of DIBELS , a program that tests fluency with nonsense words. I would always ask why we were asking struggling readers to practice reading with nonsense words when what they needed was to practice making sense with real words. DIBELS provides data though, and conversation with students about word meaning does not. We have become so data driven that we have forgetten best practice. Thanks for reminding me what is important again.

DIBELS and other programs like it are, I think, what happens when we focus only on what can be easily measured, not what’s really important. And that’s so very, very sad. But I’m glad that so many of us are trying to hold on to best practice as much as we can. I do believe that that means something. And I’m hoping that just as we’ve reached the tipping point when saving children’s lives is now being seen as more important than protecting assault weapon buyers’ rights, we might reach a point when making learning meaningful is more important than making learning easily measurable.

Truly one of the most beautifully written, inspiring and painfully true posts i’ve ever read. Thank you again for your insight.