Things have been quiet on the blog for a while, mostly because I’ve been working on several challenging projects, one of which involves writing copy for a new website that will house the blog and a variety of other resources (and hopefully be up next month)> But aware that this has been Teacher Appreciation Week, I’ve been thinking about how much both past and present teachers have impacted and contributed to my life and feeling a need to share that.

From my own days in grade school, for instance, there was the English teacher I wrote about in “My Daughter Reminds Me Why I Write (and Why She Doesn’t)”. She chose a story I’d written to submit to Scholastic’s Writing Contest—despite the fact that she was surprised that the quiet, meek girl who hardly ever spoke in class had actually written it. And last year for Teachers Appreciation Week, Heinemann shared a video of me sharing the story of how another high school teacher made me realize that, despite failing to get into AP English, I could, indeed, write insightfully about books if it’d connected to them deeply.

From my own days in grade school, for instance, there was the English teacher I wrote about in “My Daughter Reminds Me Why I Write (and Why She Doesn’t)”. She chose a story I’d written to submit to Scholastic’s Writing Contest—despite the fact that she was surprised that the quiet, meek girl who hardly ever spoke in class had actually written it. And last year for Teachers Appreciation Week, Heinemann shared a video of me sharing the story of how another high school teacher made me realize that, despite failing to get into AP English, I could, indeed, write insightfully about books if it’d connected to them deeply.

And then there’s the art teacher who instilled in me a love for visual images, the legacy of which you can see here on the blog. I took after-school art classes from her for years, first in her attic (which had sloping ceilings just like an artist’s atelier in Paris) and then in the incredible studio that extended from the back of her house. Frequently she’d create a still life for us to paint—a bowl or plate filled with apples and grapes, a jug overflowing with poppies—and in spring she’d have us take our easels outside to her garden to paint the flowers, “en plein air,” just as the Impressionists had done.

And then there’s the art teacher who instilled in me a love for visual images, the legacy of which you can see here on the blog. I took after-school art classes from her for years, first in her attic (which had sloping ceilings just like an artist’s atelier in Paris) and then in the incredible studio that extended from the back of her house. Frequently she’d create a still life for us to paint—a bowl or plate filled with apples and grapes, a jug overflowing with poppies—and in spring she’d have us take our easels outside to her garden to paint the flowers, “en plein air,” just as the Impressionists had done.

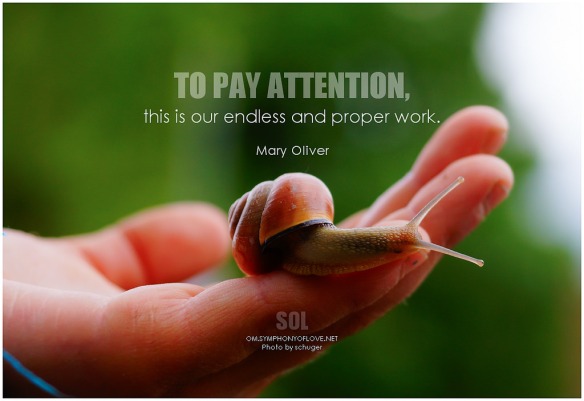

From her, I learned that looking and seeing are actually two different things, and that as poet Mary Oliver put it, in words I only discovered years later, “To pay attention, this is our endless and proper work.” But perhaps, most importantly, she made me feel that I had the sensibility of an artist, with a unique way of seeing the world—which, I think, is exactly what those English teachers did, too. They noticed something in me despite all those despites. And even though my medium turned out to be words, not markers or watercolors, each of these teachers empowered me in ways that have shaped my life.

More recently, though, I find myself inspired and impacted by teachers in a different way. Whether it’s the teachers I work with in schools, the many colleagues I have who’ve become dear friends, or those I’ve never (yet) met in person but feel like I know through twitter, it’s teachers that keep me thinking and learning—and reflecting on the question I often feel compelled to write down in my notebook:

Sometimes, this happens when a teacher says or tweets something that pushes me to reflect (in ways that aren’t always comfortable, but needed):

Sometimes it’s when an educator writes something that makes me realize that I hadn’t fully understood something that I thought I had. Recently, for instance, in his blog post, “Confronting the Disimagination Machine,” the Opal School’s Matt Karlson made me realize that worksheets are even more insidious than I’d previously thought: Not only are they not meaningful to kids, but they standardize children’s experiences and thinking in ways I hadn’t, until then, considered.

Sometimes, too, a teacher will share a project online that helps me see possibilities I’d never imagined before, which makes me incredibly happy). For example, just recently I stumbled on the work kindergarten teacher Faige Meller‘s kids’ did when she invited them to go outside and, inspired by the installation artist Andy Goldsworthy, create art from nature (which seems like the perfect antidote to the disimagination machine):

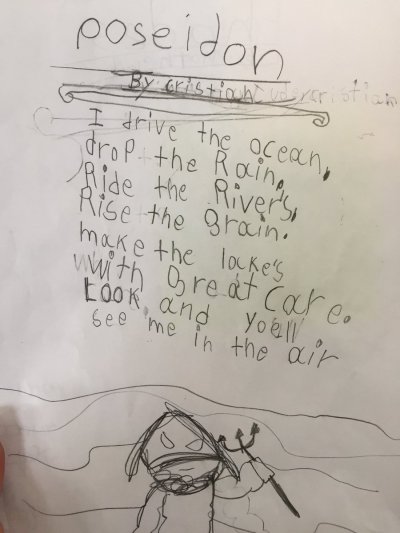

And then there’s Amy Ludwig Vanderwater, who always gets me thinking (as do Rebecca O’Dell, Alison Marchetti and the other teachers who share ideas at movingwriters.org). This year for National Poetry Month, Amy challenged herself to write 30 poems, one for each day of April, about a single subject (#1Subject30Ways), using a different poetry technique from her book Poems Are Teachers for each poem. And she invited teachers and students to join her. Amy’s subject was the constellation Orion, which inspired three of teacher Emily Callahan‘s students to write poems about Greek Mythology, like this one:

And here’s a gorgeous poem from teacher Kate Rodger, whose subject was poems about home:

Finally, there’s the teachers who invite me into their classrooms and schools to help them puzzle through problems that perplex them. Recently, for instance, I got an email from a school I’ll be starting to work with in June on embedding more meaningful grammar instruction into their middle and upper schools. And the email included the following questions, which were on their mind:

- What might a grammar curriculum across the grades look like? How do we build in inquiry/apprenticeship work from one grade to the next – should we cover the same concepts/techniques but with different (increasingly sophisticated?) mentor texts?

- How do we address student errors in addition to focusing on teaching grammar in terms of craft? How best to address grammatical errors when giving feedback on student writing?

- How do we find time to integrate inquiry grammar lessons into our curricula?

- Is there a place for direct instruction? Does it matter whether students can distinguish between a helping verb and a linking verb or a clause and a phrase? Should students learn grammar definitions, and if so, when in the process should terms be introduced? Is there ever a place for testing or quizzing students on grammar?

- How can a teacher tell if inquiry/apprenticeship instruction is effective? How do teachers encourage students to try new grammatical/stylistic techniques in their writing without having it feel forced?

I have some answers up my sleeve already, but I actually relish the opportunity to wrap my mind around these questions again and see if anything new pop up. It fact, it’s partly what keeps me going—along with remembering that paying attention is our endless and proper work.

I first ‘met’ Ellin when I read the original

I first ‘met’ Ellin when I read the original

two years ago in Reggio-Emilia where we were fellow participants in a study group exploring the implications of the Reggio approach on literacy instruction across the grade. (To read more about that experience, click

two years ago in Reggio-Emilia where we were fellow participants in a study group exploring the implications of the Reggio approach on literacy instruction across the grade. (To read more about that experience, click  thoughts and feelings, to care for and touch one another. And given that our current educational climate tends to value data points over children’s words, I understand and applaud Opal’s commitment to seeing literacy education as first and foremost concerned with offering “experiences that lead [children] to understand that they have something worth saying before caring about what others have to say.” In fact, seeing the amazing work the children and teachers were doing at Opal made me wonder if my work with reading was really big enough—and if perhaps I’m too pious and staunch in my reverence for books. But then the book lover in me kicks in again, wanting to say it’s enough, especially when students have other opportunities in other kinds of settings to recognize who they are and who they might become, as they do at Opal.

thoughts and feelings, to care for and touch one another. And given that our current educational climate tends to value data points over children’s words, I understand and applaud Opal’s commitment to seeing literacy education as first and foremost concerned with offering “experiences that lead [children] to understand that they have something worth saying before caring about what others have to say.” In fact, seeing the amazing work the children and teachers were doing at Opal made me wonder if my work with reading was really big enough—and if perhaps I’m too pious and staunch in my reverence for books. But then the book lover in me kicks in again, wanting to say it’s enough, especially when students have other opportunities in other kinds of settings to recognize who they are and who they might become, as they do at Opal.

Before jumping on the Bolt Bus to D.C., however, I’ll be heading half-way around the world to the city of Doha in Qatar. In addition to working for several days with teachers (and my Reggio-Emilia comrade, Katrina Theilmann) at the American School in Doha, I’ll be facilitating a two-day workshop on “Teaching the Process of Meaning Making in Reading,” as part of the

Before jumping on the Bolt Bus to D.C., however, I’ll be heading half-way around the world to the city of Doha in Qatar. In addition to working for several days with teachers (and my Reggio-Emilia comrade, Katrina Theilmann) at the American School in Doha, I’ll be facilitating a two-day workshop on “Teaching the Process of Meaning Making in Reading,” as part of the  Ohio to Iowa to California, through the blogosphere.

Ohio to Iowa to California, through the blogosphere. After that I’ll be in Portland, Oregon, December 9 and 10, presenting a workshop for educators sponsored by

After that I’ll be in Portland, Oregon, December 9 and 10, presenting a workshop for educators sponsored by  And finally, after what I hope will be two balmy days in Los Angeles in January working with LAUSD’s wonderful Education Service Center South coaches and teachers, I’ll be heading north to wintery Toronto for the

And finally, after what I hope will be two balmy days in Los Angeles in January working with LAUSD’s wonderful Education Service Center South coaches and teachers, I’ll be heading north to wintery Toronto for the